Three horizons of sustainable food innovation

Table of Contents

i. Moving away from zero-sum food futures

In a previous essay, we argued that a ubiquitous term like ‘sustainability’ is probably best understood as functioning within multiple paradigms. Some, like ecomodernism and degrowth, appear to be fundamentally opposed, shaping food innovation (and much more) in radically different directions, yet both in the name of sustainability. These tensions make the future of food seem like a zero-sum game. How might they be resolved?

In a liberal democracy, one classic response might be that everyone should get to share their opinion, that debate is inherently valuable, and that the ‘marketplace of ideas’ will eventually yield the best solutions. However, merely citing a diversity of opinions without incorporating them into action is, if the status quo is harmful, not only insufficient but irresponsible, since ultimately nothing changes. The inertia of existing power structures means that, in the absence of deliberate intervention, dominant economic and technological forces will continue shaping and reshaping the food system, often reinforcing the very problems we aim to solve. In this sense, the ‘marketplace of ideas’ is not neutral, but naturally shaped by contemporary interests and concerns.

How do we preserve that well-intentioned and crucial spirit of listening whilst also making it actionable? How do we create a process where opposing visions don’t simply compete for sole dominance, but actively inform, challenge, and complement each other in productive ways?

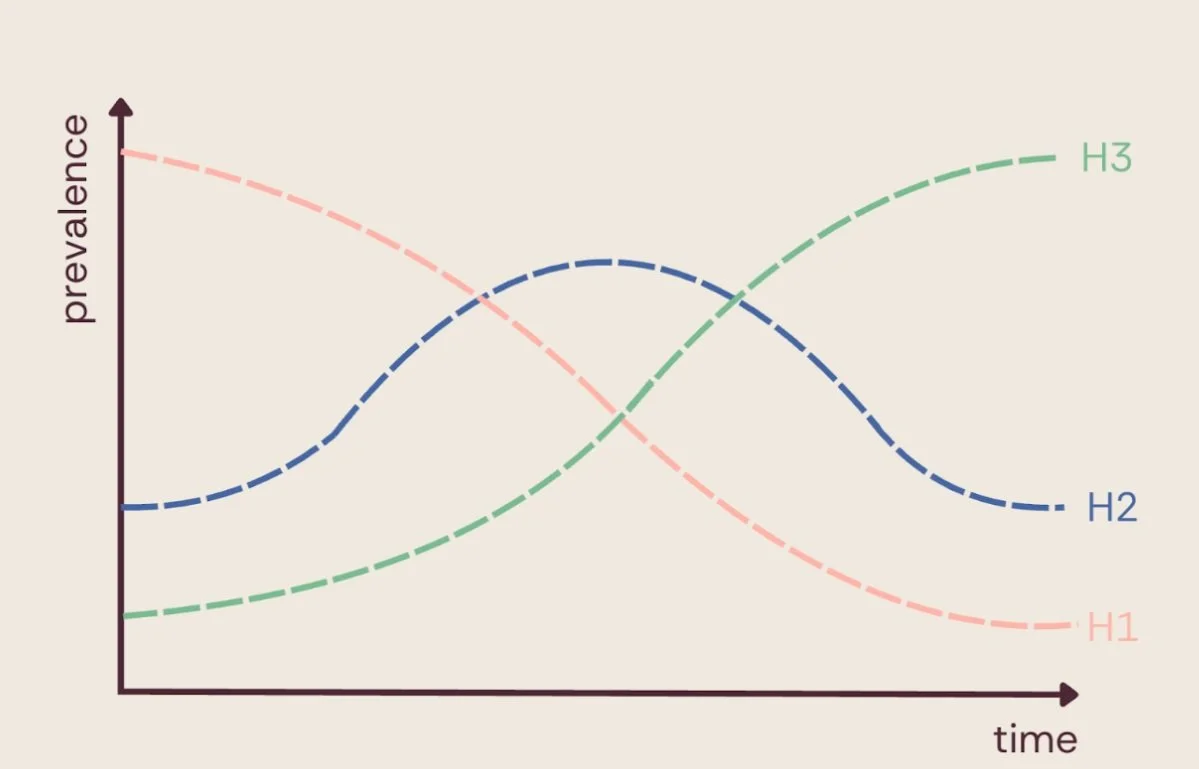

One approach we have found helpful is the Three Horizons Framework (Figure 1), developed by Bill Sharpe and others¹. The framework structures how we can think about change over time—not as a linear path, but as an ongoing negotiation between present realities, emerging innovations, and long-term transformations. For an introduction to this framework, we suggest you watch economist Kate Raworth’s brief explainer video before continuing.

Figure 1: Three Horizons Framework. Adapted from ITC Foresight Toolkit.

ii. More constructive conversations on sustainable food innovation

The Three Horizons Framework helps us move beyond unproductive, bifurcated, polarising debates—like whether or not we should replace all animal products with plant analogues—to avoid the paralysis of believing that if no single vision prevails, then none is possible to achieve.² It encourages us to acknowledge that different actions serve different functions over different time horizons, and that progress is neither linear nor zero-sum.

It invites us to recognise the value of those working to ‘feed the world’ today and sustain existing systems (H1/incrementalists), even if that alone is insufficient. It asks us to appreciate the importance of bold, long-term visions to guide strategic priorities (H3/visionaries) and the need for those tinkering and trying things, testing pathways from present realities to future possibilities (H2/innovators). It shows us how none of these horizons alone is enough, and that all are necessary to work towards desirable futures. The framework is not about purity, or ensuring every action we take aligns with our ideal vision of the future. Nor does it require that all actions play the same role over the same time horizon in shaping that future. Each might have bigger or smaller, and shorter- or longer-term parts to play. Instead, it invites us to focus on finding common ground for dialogue at any and every given point in a process, recognising each other’s contributions and acknowledging that no horizon can do it all itself. It equips us to assess what is useful and to what extent, keeping what works, discarding what doesn’t, iterating, and bringing together different voices—each with a distinct but valuable role to play over different timeframes.

The framework can help structure such discussions with questions like those Kate Raworth presents in her video.³ We find particular promise in weaving in questions informed by the discipline of Science and Technology Studies (STS) to help shape innovation towards our preferred future—examples of which we’ll use to colour the next section. Provocations like these can help foster empathy and understanding between different ambition levels, untangle tensions between different visions of the future, and encourage us to think more strategically about how sustainable food innovation could bring them into reality.

iii. Three horizons of upcycling

To illustrate more concretely how the Three Horizons Framework helps us hold space for multiple approaches, we can look at upcycling—a practice that takes many forms, some of which may feel incompatible. It invites us to recognise the role of both immediate, practical responses and longer-term visionary shifts that evolve with the food system, each contributing in different ways over different timescales.

Today, upcycling often uses food by-products produced at an industrial scale, like brewer’s spent grain (BSG) from large-scale breweries, oil presscakes or sugarcane bagasse. This makes a lot of sense. The primary goal of upcycling is to reduce waste and transform it into edible food, so focusing on by-products produced in larger quantities could have a larger impact. However, if upcycling remains an add-on to ultimately degrading industrial processes, it risks entrenching the system it aims to improve. At the moment, it mostly doesn’t ask the deeper question: what foods should we be producing in the first place, and how?

This doesn’t mean it's without value. Rather than dismissing it outright, we might see this kind of H1 upcycling as a valuable but flawed first step—one to be critically engaged with and iterated upon in service of deeper transformation.

To guide such reflection, we might ask:

How can we balance the goal of making use of existing by-products with the need to transform the systems that produce them?

How might upcycling perpetuate or disrupt the commodification of foods and their by-products, and who does it ultimately serve?

Guiding questions informed by STS and other critical disciplines can help ensure that upcycling reaches its transformative potential, such that today’s innovations contribute to preferred futures (H2+) rather than reinforcing the existing system (H2-). To do so, we must keep an ambitious H3 vision in mind, asking questions like:

What types of food by-products would exist in an absolutely and justly sustainable food system, and how could upcycling adapt to use them?

How can upcycling contribute to food justice and sovereignty rather than just efficiency and profitability?

What ownership and governance models for upcycling could prevent it from reinforcing corporate control over food systems?

If these questions support H2+ interventions, we might also consider complementary questions that can help transform H2- ones into H2+. Provocations here might include:

Who stands to benefit most from current upcycling innovations, and who is being excluded?

How could upcycling technologies be more justly oriented to support equitable access and distribution of benefits?

How can intellectual property models be structured to prioritise social good over profit-driven exclusivity?

Whatever the future holds, it will inevitably be messy. The more consciously we navigate this messiness, the better. The Three Horizons Framework is not about forcing consensus or diluting ambition but creating space for productive tensions, where different paradigms challenge, refine and inform one another rather than talking past each other. By recognising the value of multiple approaches across different timescales, we can move beyond zero-sum thinking. H3 visionaries can see H1 incrementalists not as obstacles to change but as key allies in scaling emerging solutions, whereas H1 thinkers can, in turn, draw inspiration from H3’s long-term ambitions. Meanwhile, H2 innovators must bridge the gap, ensuring that today’s experiments align with meaningful transformations rather than reinforcing the status quo.

We are certainly not the first to suggest this, but we believe and have experienced that the more those of us (usually H3-inclined) working in food system transformation adopt this framework, the more we can foster better conversations and more meaningful collaborations with partners across the horizons, even if our preferred futures don’t always align.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Eliot and Josh conceived this essay together. Eliot wrote the first draft, Josh provided editorial input, and they developed it further together.

Header image credit: Rick Guidice (1975) ‘Cylindrical Colonies, interior view’, NASA Ames Research Center History Archives.

Related posts

Endnotes

[1] This framework was developed and iterated on collaboratively, with notable contributions from Anthony Hodgson and Bill Sharpe (2007), ‘Deepening futures with system structure’, In: Scenarios for Success: Turning Insights Into Action, Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA.; Andrew Curry and Anthony Hodgson (2008) ‘Seeing in Multiple Horizons: Connecting Futures to Strategy’, Journal of Future Studies; and Bill Sharpe et al (2016) ‘Three horizons: a pathways practice for transformation’, Ecology and Society.

[2] The sustainability paradigms we’ve discussed elsewhere don’t all directly map 1:1 onto each of the Three Horizons, nor are they intended to. Some, like relative sustainability, probably don’t go beyond H2-, whereas other like degrowth could act as guiding H3 visions but don’t really have any H1 dimension.

[3] Kate Goodwin helpfully summarised these questions here.