Paradigms of sustainability

This essay is part of a series that explores the intersections of sustainability, food innovation and food culture. The series grew in part from an internal discussion on what our research group name—the Sustainable Food Innovation Group—might mean to different people, and different food futures the name might conjure up. In Part I, we examine some of the various and often conflicting framings that are mobilised under the same banner of sustainability. In later essays we will explore how the differences between sustainability paradigms might be reconciled and how innovation might be guided towards our preferred futures using a tool called the Three Horizons Framework; our approach to innovation and how food cultural research can guide us to do better food innovation; and how food innovation and agroecology can support each other. We hope that this series can contribute to more nuanced and fruitful discussions on what sustainable food innovation can be, and what it can hope to achieve.

Table of Contents

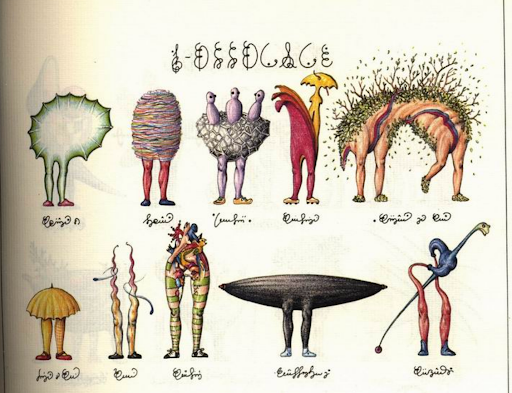

Figure 1: People have long imagined what the future of food might look like.¹ When future historians look back on some of the dominant ideas of today, might they be looked on as quaintly as we today view the Retrofuturist ideas of the 1960s & 70s?

i. A nebulous concept

The term ‘sustainability’ has been used in many ways throughout its history and today, there are multiple, often competing interpretations, all mobilised under its banner. It has been described as one of the most ‘ubiquitous, contested and indispensable concepts of our time… the term suffers from clichéd use… turning it into a fuzzy, empty and imprecise shell for a wide public’². Because of this fate, it has been argued that one ‘can’t use the term sustainability in a general setting and be confident of being understood’.³

Different interpretations of sustainability involve different value systems, which envision different food futures and prioritise—and exclude—different types of food innovation to get there. Awareness of this values-based selectivity can help us think more critically about who stands to win or lose in each of those futures, and what some of the consequences of each, intended or not, might be.

This essay grew in part from an internal discussion on what our name—the Sustainable Food Innovation Group—might mean to different people, what values they might assume we have, and the different food futures the name might conjure up.

ii. Paradigms of sustainability

Here we describe some of the dominant paradigms of sustainability that we’ve come across, before reflecting on how their different values influence the types of futures—and food innovations that would get us there—they permit or don’t.⁴ Some of these paradigms are incompatible with each other (e.g. relative vs absolute sustainability) but others are not necessarily (e.g. absolute sustainability and degrowth). Furthermore, some of the paradigms are about more than ‘just’ sustainability, as will become clear. Still, we felt assured in including them here in that they are all concerned with ensuring the persistence, if not flourishing, of humanity and ecology, and illustrate the breadth of ways that have been put forward to achieve that aim.

a. Relative sustainability

We begin with what real sustainability probably isn’t.

Sustainability has warped into a myriad of incremental approaches that lack a coherent long-term vision for system transformation. They are often global and top-down rather than place-based and context-specific, and are more about

simply doing less harm, rather than changing the harm’s source. They pay lip service to real change. Many decry this paradigm as a co-option, that ‘undermine[s] actual sustainability by creating an illusion of meaningful change’, leading some to reject the term ‘sustainability’ outright.⁵

Corporate interpretations, like Environmental Social Governance (ESG), epitomise this paradigm. Here, sustainability is largely permitted only to the extent that shareholder returns can be maximised in the short-term, or as a tool for attracting and retaining investors, or for managing risks by adhering to existing (and insufficient) certification and reporting standards. It is built on the assumption that the ecological crisis can be solved by tweaking or optimising the current extractive system in service of ‘green growth’, in lieu of more radical system change. If the impacts of products or businesses are quantified, they are typically presented as ‘X% less impact’, against a reductionist set of metrics, without any wider context to evaluate how ‘good’ that is and whether it is ‘good enough’—so-called ‘relative sustainability.’

This gap between rhetoric and action has, in many cases, led to accusations of greenwashing. Research from the World Benchmarking Alliance highlights this disconnect: as of 2023, only 13 of the world’s 350 largest food and agriculture companies had set science-based targets for climate action, while over 165 had yet simply to disclose any meaningful commitments—let alone implement them.⁶

While many well-intentioned actions happen within this paradigm and can make some kind of difference, the paradigm itself constrains our ability to achieve the kind and degree of sustainability that is needed. As climate change scientist Professor Kevin Anderson witheringly affirms: ‘the climate does not respond to good intentions, Machiavellian policies, eloquent arguments, legal niceties, promises of tech tomorrow or accountancy scams… all are trumped by the brutal beauty of physics.’ Of course, as important as climate change is, ‘sustainability’ encompasses more than that, including complex and irreducible social, ecological, cultural, and ethical dimensions. Yet Anderson’s core insight remains broadly applicable: across all domains of sustainability, real progress demands confronting biophysical realities, not just hot air, symbolic gestures or good intentions.

b. Absolute sustainability

The Planetary Boundaries framework defines the Safe Operating Space (SOS) for humanity by quantifying the limits for Earth’s natural systems. These boundaries represent biophysical thresholds that, if exceeded, increase the risk of destabilising the planet's life-support systems.⁷ As of 2023, six of the nine Planetary Boundaries have been crossed—biosphere integrity (genetic and functional), climate change (CO2 concentration and radiative forcing), novel entities, biogeochemical flows (P and N), freshwater change (Green and Blue), and land system change. Only three remain within the SOS—stratospheric ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol loading, and ocean acidification, although the latter is thought close to being exceeded.⁸

Absolute sustainability takes the approach of allocating portions of the SOS to individual humans (downscaling) before aggregating those allocations at different scales e.g. for food products, or the food system and its constituent parts (upscaling).⁹ An ‘absolute environmental sustainability assessment’ (AESA), proponents argue, is, therefore, an objective, binary determination: if a product or industry uses less than or equal to its allocated portion of the overall SOS, it is sustainable, whereas if it exceeds its allocated portion, it is unsustainable.

While on the surface the absolute sustainability paradigm may seem satisfyingly unambiguous and straightforward, its conceptual clarity belies multiple operational challenges: for example, how exactly to calculate allocations. Important work has been undertaken recently to develop allocation methods that are equitable and just, including by colleagues at DTU’s Center for Absolute Sustainability.¹⁰ Since selecting an allocation method is value-laden and always has ethical tradeoffs, it is not something that can be answered by purely technical means. For example, the extent to which industrialised countries should bear a greater burden for reducing their impact (i.e. be allocated less of the SOS) since they have greater liability for the ecological crisis is a highly consequential ethical judgement. How human socio-economic conditions should be assessed within this framework also remains an open question. Some related frameworks that attempt to answer these types of questions include Doughnut Economics, ArkH3’s ‘Sustainability-As-The-World-Needs’, and Degrowth (see section e).

c. Ecomodernism

Ecomodernism argues that the ecological crisis is a purely technical problem that can be solved by intensifying food production, and ultimately decoupling it from land, energy, and resource use.¹¹ Its proponents argue that minimising the land footprint of food production and other human activities would allow us to spare land for ecosystem restoration to ‘make room for nature’.¹²

There is a range of opinions within the paradigm on how this decoupling should happen. Some Ecomodernists advocate for increasing crop yields through the precision application of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, using GMO crop varieties, increasing mechanisation and technologisation of agriculture, and intensifying meat production and aquaculture.¹³ Others go further, arguing that technologies such as cellular agriculture, lab-grown meat, vertical farming and insect cultivation should largely replace conventional agriculture in a post-agriculture future.¹⁴ This is the dominant, Silicon Valley, venture capitalist mode of innovation and is what a lot of people think about when they hear the words ‘food innovation’.

This idea is built on the narrative of ‘progress’, modernisation, and increasing human living standards globally by ‘liberating people from the drudgery of agricultural work’ through technological innovation and economic growth, using ‘humanity’s extraordinary powers in service of creating a good Anthropocene.’¹⁵ It is also based on a dualist conception of nature, in which humans and nature are considered ontologically separate.¹⁶

Many questions raised by this paradigm remain open, including whether agricultural intensification would actually result in ecosystem restoration on spared land (Jevons’ Paradox famously suggests otherwise), and if so how; what the energy requirements of the proposed technologies are and where this energy would come from; what the unintended consequences of these technologies might be; whether this model reduces or exacerbates existing power dynamics, injustice and inequality; and what novel food cultures an Ecomodernist paradigm would give birth to.¹⁷

d. Agroecology & regeneration

Agroecology and regeneration are two related approaches that at their best have much in common, yet also important differences. ¹⁸

Agroecology applies the science of ecology to agriculture and the food system while also serving as a transformative socio-political movement. It is grounded in 13 principles, including soil health, biodiversity, reduced external inputs, social values and diets, fairness, and land and natural resource governance.¹⁹

Agroecological systems embrace diverse cropping methods, polycultures, agroforestry, and the integration of animals into healthy agroecosystems. They foster a mosaic of wild and cultivated landscapes—standing in stark contrast to Ecomodernist ideas of separation and decoupling.

With roots in Indigenous agriculture and agrarian grassroots political movements, to many of its proponents, agroecology is inseparable from struggles for decolonisation, food sovereignty, equity, and justice. Knowledge is developed bottom-up, through community-led and traditional practices, rather than imposed top-down by scientific institutions or policy-makers—though the latter two can also be crucial enablers and partners.

Though agroecology is well-defined, it is increasingly being diluted through co-option—its principles simplified, misrepresented, or reduced to false equivalencies—in which productivity remains the primary goal, and deeper transformation is constrained by entrenched systems of power and global commodity markets.²⁰

‘Regeneration’ is an even more contested term within food systems. Its interpretations vary widely, though they generally fall along a spectrum. At one end, regeneration shares much with agroecology, advocating for deep, systemic transformation in which agroecosystems are seen as complex living systems, and humans act as keystone species and stewards of the land.²¹

Proponents of this view argue that regeneration requires not just practical changes but a fundamental shift in mindset—an internal, ethical, philosophical, and sometimes spiritual transformation.²²

At the other end of the spectrum, ‘regeneration’ is being co-opted.²³ Corporate actors frequently adopt a shallow, ‘apolitical’ version of the term; which is to say, its politics are about supporting the status quo. Here, regeneration is framed as a set of incremental improvements—such as reducing tillage or replacing synthetic fertilisers with green manures—without challenging the broader system. This kind of so-called ‘regeneration’ arguably has more in common with relative sustainability than agroecology. This version assumes that agri-food corporations will and should continue to play a dominant role in how agri-food systems work, and that consumers should still be able to purchase all their favourite products (but now regenerative!) to drive so-called ‘green growth.’

Some people view regeneration as a more ‘evolved’ and mutually exclusive successor to sustainability. We think this rejection of ‘sustainability’ is mostly of relative sustainability specifically, as some more rigorous paradigms of sustainability have much more in common with regeneration than things that divide them. One way of reconciling the two concepts that we quite like is a relational framework of ‘authentic’ sustainability and regeneration. In this discussion Bill Baue argues that sustainability and regeneration are related and interdependent terms and that it is ‘not particularly useful to compare them in a hierarchical format.’ He continues that ‘regeneration is an ongoing process, whereas sustainability is an outcome… can that regeneration sustain itself… with resilience?’ In other words, regeneration is how we can improve the degraded status quo, and authentic sustainability is how we can keep it.

The contested nature of this paradigm leaves many open questions, including what should count as agroecological or regenerative and who gets to decide; which food system actors should be involved to what extent and what their role is; and how an actor can ‘prove’ that their actions are agroecological or regenerating, amongst many others.

e. Degrowth

Degrowth is an emerging, contested and often misunderstood paradigm that rejects the idea that sustainability can be achieved at all in a growth-oriented economy. It argues that GDP is a poor measure of the success of society as ‘it's not aggregate production that matters but rather what we are producing, whether people have access to the essential goods they need and how income is distributed.’ ²⁴

Proponents of degrowth advocate for an overall reduction in production and consumption to move into the SOS for humanity per the Planetary Boundaries Framework (see the section on absolute sustainability) whilst maintaining equitable human and ecological flourishing. It is based on three primary values²⁵ :

Equality and justice, through more equitable access to resources and decolonisation; solidarity with social movements worldwide, including/especially the so-called Global South.

Sufficiency, based on the understanding that a good life filled with prosperity and well-being is not determined by or conditional on increasing material consumption.

Economic democracy, which argues for a more democratic and participatory model for the economy, to democratically determine how wellbeing should be prioritised, what the finite ‘budget’ of the SOS should be allocated to or ‘spent on’, and which less necessary sectors and industries should be scaled down.

There is an emerging body of literature that explores how the food system could look within a degrowth paradigm, with many conceptions built upon ideas of agroecology described in the previous section, with a particular focus on communal practices.²⁶

Open questions include: how would economic democracy work in practice, and how can it be ensured that it achieves a food system aligned with degrowth; how do we avoid unintended consequences; how can we overcome the growth imperative; and if it is utopian and/or unrealistic.

iii. What might sustainable food innovation look like in each of these paradigms?

Since each sustainability paradigm is motivated by different values, goals, and visions for the future, food innovation done in the name of sustainability looks quite different in each paradigm.

In Table 1 we look at two examples of sustainable food innovation that are integral to our research program—upcycled foods and plant cheese—and see how they might look different within each sustainability paradigm. It becomes quickly apparent that the same innovation, even if always done in the name of sustainability, would in each paradigm look very different.

| Paradigm of sustainability | Driving principles of innovation | What might food innovation look like in each paradigm? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upcycled foods | Plant cheese | ||

| Relative sustainability | Minimisation of harm to meet (insufficient) ESG targets. Corporate-friendly solutions that fit within current production and retail structures, and don’t fundamentally challenge the existing food system or address its deeper problems. | Mainstream food brands have incorporated some upcycled ingredients into some product lines, resulting in the partial reduction of industrial by-products, but plenty remain underutilised. | Ultra-processed plant cheeses are made using a long list of industrially produced ingredients (oils, starches, enzymes) and crops grown in high-input monocultures. |

| Absolute sustainability | Food products must pass an ‘absolute sustainability assessment’ to determine if they stay within Planetary Boundaries. This could be achieved through different methods, so long as the food system functions within its allocated portion of the SOS. | A wide array of ‘absolutely sustainable’ upcycled food products are made from both the by-products of the industrial food system and sustainably produced ingredients, to move the food system to within its allocated portion of the SOS. | Plant cheeses are made using ingredients and processing methods that are ‘absolutely sustainable’, to move the food system within its allocated portion of the SOS. |

| Ecomodernism | Decoupling food production from land, water, and emissions through corporate-led efficient and scalable technological innovation, but without attention to sociopolitical matters of equity, sovereignty, justice, and cultural appropriateness. | Food production is integrated into a hyper-efficient circular bioeconomy, in which industrial food by-products are converted into foods/food ingredients, or toward other circular uses e.g. pharmaceuticals and agricultural inputs, using biotechnology and other technological solutions. | Plant cheeses are made from intensively produced industrial plant ingredients, possibly genetically modified for optimal cheese-making properties, or grown in vertical farming systems, and other ingredients made from precision fermentation of engineered microbes (if cheese is even still considered an appropriate form). |

| Agroecology & regeneration27 | Food innovation is aligned with agroecological principles (like soil health, biodiversity, fairness, social values and culturally appropriate diets). Food products are designed around healthy agroecosystems and use all their outputs as ingredients. | Upcycling is used to support healthy agroecosystem design, complementing other ways of recycling resources, like composting. This allows more food to be produced from the same amount of land. Upcycling innovation involves the revival of traditional/cultural practices. | Plant cheeses are made with minimally processed bioregionally appropriate ingredients sourced from local, healthy and resilient agroecosystems. They co-exist alongside cheese made from agroecological animal products from the same agroecosystems. |

| Degrowth |

Food innovation is driven by principles of equality and justice, sufficiency and economic democracy, whilst bringing the food system within the SOS. One mode is communal practice embedded within decentralised, commons-based, cooperative, and localised economies rather than market-driven product categories. |

Upcycling is a tool to bring the food system within its allocated portion of the SOS, replacing higher-impact foods determined through economic democracy. Upcycling practices are likely similar to those in the ‘agroecological regeneration’ paradigm, with particular emphasis on communal infrastructure, both low and high-tech, like communal kitchens and biorefineries. |

Plant cheese is a tool to bring the food system within its allocated portion of the SOS, largely replacing higher-impact animal products, determined through economic democracy. Cheeses are likely made similarly to those in the ‘agroecological regeneration’ paradigm, with particular emphasis on communal practice e.g. fermentation-based legume cheeses made in a worker’s cooperative. |

We see value in aspects of multiple paradigms for a truly sustainable food innovation. More ambitious visions of agroecology align closely with our commitment to a socially just food system built on resilient, biodiverse agroecosystems. Meanwhile, the absolute sustainability perspective serves as a crucial reminder that quantifying biophysical impacts is essential and that the SOS can steer innovation—though is insufficient on its own without also addressing social and ethical dimensions. The degrowth paradigm is one way of adding this social dimension, challenging us to rethink how the food system is structured, whom it serves, and for what purpose. At the same time, while we question Ecomodernism’s emphasis on corporate control and power, we acknowledge that some elements often associated with this paradigm—like biotechnology—could be valuable if oriented in service of a ecological, equitable, and flavourful food system.

We also think that some important dimensions of sustainability aren’t given enough attention among these paradigms. Food culture—all the qualitative, hard-to-measure, sometimes idiosyncratic reasons why people eat the way they eat—is not nearly as central as it could and perhaps should be.²⁸ Nor are flavour, pleasure, delight and the enjoyment of food given the attention they merit. After all, a food can be the most sustainable by any metric, but if people don’t want to eat it, does it even really matter? In a future essay, we will explore how sustainability doesn’t have to be a chore or a compromise, but rather can be a source of pleasure, creativity and joy—and how valorising and harnessing these aspects of the human experience can play a crucial role in making sustainability of any kind not only achievable but desirable.

The different paradigms we have explored in this essay reflect fundamentally different views about what sustainability is and how it should be achieved through food innovation and beyond. Taken together, these differences might seem irreconcilable. We propose they need not be. In a later essay, we will explore one way to reconcile these tensions, using the Three Horizons Framework.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Eliot and Josh conceived this essay together. Eliot wrote the first draft, Josh provided editorial input, and they developed it further together.

Image credit: Moon Metropolis, Roy Scarfo, 1965

Planetary Boundaries Framework image credit: Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Related posts

Endnotes

[1] Warren Belasco (2006), ‘Meals to come: a history of the future of food’, University of California Press: Berkeley, USA. An illuminating book that explores humanity’s ‘deep-seated anxiety about the future of food’, which has a much more storied history that many might imagine.

[2] Tobias Luthe and Michael von Kutzschenbach (2016), ‘Building Common Ground in Mental Models of Sustainability’, Sustainability and Climate.

[3] Why it's not sustainability vs. regeneration - Bill Baue & Daniel Wahl in dialogue

[4] This list is neither mutually exclusive nor jointly exhaustive. Rather than aiming for it to be a comprehensive overview of every paradigm of sustainability ever conceived, we simply hope to summarise some of the most dominant paradigms that seem most pertinent to us and our work. For a more complete terminological history, see: Ben Purvis, Yong Mao, Darren Robinson (2019), ‘Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins’, Sustainability Science.; Jeremy Caradonna (2014), ‘Sustainability: a History’, Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK.

[5] Leah Gibbons (2020), ‘Regenerative—The New Sustainable?’, Sustainability.

[6] World Benchmarking Alliance (2023), ‘2023 Food and Agriculture Benchmark’,World Benchmarking Alliance. A science-based target for climate change is defined as setting a target to reduce company GHG emissions (scopes 1, 2 and 3 per the GHG Protocol) to a level aligned with 1.5℃. See here for more.

[7] Catherine Richardson et al. (2023), ‘Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries’, Science.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Anjila Wegge Hjalstad et al. (2020), ‘Sharing the safe operating space: Exploring ethical allocation principles to operationalize the planetary boundaries and assess absolute sustainability at individual and industrial sector levels’, Journal of Industrial Ecology.; Yan Li, Ajishnu Roy and Xuhui Dong (2022), ‘An Equality-Based Approach to Analysing the Global Food System’s Fair Share, Overshoot, and Responsibility for Exceeding the Climate Change Planetary Boundary’, Foods.

[10] Johan Rockström et al. (2023), ‘Safe and just Earth system boundaries’, Nature.; Joyeeta Gupta et al. (2023), ‘Earth system justice needed to identify and live within Earth system boundaries’, Nature.; Anjila Wegge Hjalsted et al (2020), ‘Sharing the safe operating space: exploring ethical allocation principles to operationalise the planetary boundaries and assess absolute sustainability at individual and industrial sector levels’, Journal of Industrial Ecology.

[11] Linus Blomqvist, Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger (2015), ‘Nature Unbound: Decoupling for Conservation’, The Breakthrough Institute.

[12] John Asafu-Adjaye et al (2015), ‘An Ecomodernist Manifesto’, The Breakthrough Institute.

[13] Helen Breewood and Tara Garnett (2022, ‘What is ecomodernism?’, Table Debates. This is a brilliant primer on the topic that we encourage people to read. This former conception of this paradigm shares much with sustainable intensification, another related and disputed concept that seeks to increase agricultural production whilst minimising its impacts and land footprint.

[14] George Monbiot (2022), ‘Regenesis: Feeding the world without devouring the planet’, Penguin: London, UK.

[15] John Asafu-Adjaye et al (2015), ‘An Ecomodernist Manifesto’, The Breakthrough Institute.; Helen Breewood and Tara Garnett (2022), ‘What is ecomodernism?’, Table Debates.

[16] Kristin Hällmark (2023), ‘Politicization after the ‘end of nature’: The prospect of ecomodernism’, European Journal of Social Theory.

[17] Chris Smaje wrote ‘Saying No to a Farm Free Future’ in response to George Monbiots ‘Regenesis’, in which he debunked many of the latter’s Ecomodernist claims. This essay, ‘George and the Food System Dragon’ by Jim Thomas, summarises the debate well.

[18] Some readers might baulk at our lumping together of agroecology and regeneration in the same paradigm. We’ve chosen to include both together for brevity, even if what is meant by these terms is sufficiently wide-ranging that they could each arguably be split into multiple paradigms, and certainly even merit an entire essay.

[19] Agroecology Europe, ‘Consolidated Set of 13 Agroecological Principles’.

[20] Beatrice Walthall, José Luis Vicente-Vicente, Jonathan Friedrich, Annette Piorr, Daniel López-García (2024), ‘Complementing or co-opting? Applying an integrative framework to assess the transformative capacity of approaches that make use of the term agroecology’, Environmental Science and Policy.

[21] Ethan Soloviev (2021), ‘Paradigms of agriculture’, Self-published.

[22] Daniel Christian Wahl (2016), ‘Designing Regenerative Cultures’, Triarchy Press: Charmouth, UK.

[23] Beatrice Walthall, José Luis Vicente-Vicente, Jonathan Friedrich, Annette Piorr, Daniel López-García (2024), ‘Complementing or co-opting? Applying an integrative framework to assess the transformative capacity of approaches that make use of the term agroecology’, Environmental Science and Policy

[24] Timothée Parrique (2023), Twitter thread on ‘The impossibility of green growth and the necessity of degrowth’; Jason Hickel, addressing Dutch Parliament.

[25] Jason Hickel (2020), ‘Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World’, Penguin: London, UK.

[26] Leonie Guerrero Lara et al. (2023), ‘Degrowth and agri-food systems: a research agenda for the critical social sciences’, Sustainability Science.; Julien-François Gerber (2020), ‘Degrowth and critical agrarian studies’, The Journal of Peasant Studies.; Anitra Nelson and Ferne Edwards (2021) ‘Food for Degrowth: Perspectives and Practices’, Routledge Environmental Humanities..

[27] We’re using an example of transformative agroecology here, rather than mere regeneration or co-opted versions of either.

[28] It is one of the 13 principle of agroecology, but even then one that isn’t as widely discussed as others like soil health or fairness.