Agroecological food innovation

This essay is a companion piece to two of our earlier works. In ‘Innovation is Multiple’, Josh developed the idea of ‘amodern’ innovation, an alternative to the zero-sum binary of (modernist) innovation vs (anti-modernist) tradition that often distorts and limits discussions around the future of food. We invite you to read that paper if you are interested in going deeper into the conceptual groundwork. In ‘Reclaiming Innovation’, Eliot and Josh expanded upon the idea of amodern innovation, looking at it from food culture and food sovereignty perspectives. In both these papers, we used agroecology as an illustrative example of how innovation and tradition are not zero-sum and how our preferred futures would be best served by an amodern approach to agroecological innovation. In this third essay, we wanted to explore what that could look like in more detail.

Table of Contents

Food innovation and agroecology are much more compatible than is sometimes assumed. Food innovation is far from the exclusive domain of Silicon Valley VC-backed technocrats. And agroecology has always been innovative, drawing on traditional, indigenous and folk knowledge and practices that are themselves all the accretions of past innovations, even if they don’t use the ‘i word’. To thrive in an ever-changing future, agroecology must continue to evolve, and we argue that agroecological food innovation can be a powerful part of that evolution.

i. An antidote to solutionism

Discourse on the future of food abounds with ecomodernist techno-fix solutionism, like cell-cultured meat and precision fermentation. These technologies are often presented by advocates as frictionless silver bullets. Yet these so-called solutions are often arrived at without a grounded understanding of the problem they claim to solve, ignore crucial context and complexities and gloss over their tradeoffs and shortcomings.¹

Agroecology is a popular alternative among those who reject technological solutionism. It first arose as an approach that applies ecological science to agricultural systems, and has since evolved to offer a hopeful, transformative socio-political vision for the food system rooted in equity, justice and food sovereignty.² Yet here too, some advocates risk falling into a similar trap, presenting agroecology as a catch-all answer without honestly grappling with its own trade-offs and limits. Scholar Garrett Broad has termed this tendency ‘agroecological solutionism.’³

For example, most proponents of agroecology agree that integrating animals into agricultural landscapes is essential for agroecosystem health.⁴ Many also acknowledge that agroecological systems would likely produce less (but ‘better’) meat and milk than in today’s extractive industrial food system. Yet exactly how much meat and milk they could yield is often left unexamined. Some studies suggest it may be very little, perhaps just a few grams per person per day, if grazing were to remain within ecological limits.⁵

Some agroecological proponents suggest that any protein shortfall that follows reduced meat production—the so-called ‘protein gap’⁶—could be met solely through increased consumption of unprocessed whole plant foods like legumes.⁷ While we agree that these foods are important for more sustainable diets, it is overly simplistic to suggest that they alone could address the protein gap—not because enough protein couldn’t be produced, but because that type of diet might not work for all eaters. As Broad says, it’s often taken for granted in agroecological circles that ‘everyone wants to eat local, seasonal diets with minimal meat… like Alice Waters or Michael Pollan…’, but this isn’t necessarily so.⁸ Many eaters value convenience, familiarity and sensory pleasure that whole foods like beans can’t always satisfy (as delicious as they can be when prepared well). And that’s okay. If agroecology is to offer a realistic and inclusive vision for the future of food that doesn’t ignore biophysical limits or food-cultural realities, shortcomings like these must be addressed.

This is where food innovation grounded in agroecological principles could come in.

ii. What might agroecological food innovation look like?

We recognise that many agroecologists are sceptical of ‘innovation’ as the term is so entwined with techno-fix solutionism, which is at odds with agroecological principles. But innovation need not be only like that. Agroecology can be strengthened by reclaiming innovation, rather than rejecting it outright. Farmers, after all, have been innovating long before the term existed. Today, agroecological practitioners continually innovate by developing seed varieties, stacking complementary enterprises, designing multifunctional agroecosystems and developing human-scale tools, to name just a few practices that blend novel ideas with a rich body of traditional, local and Indigenous knowledges. Food innovation done well can be another addition to that toolbox of practices.

To imagine what food innovation that is aligned with agroecological principles could look like, we use the ‘10 Elements of Agroecology’, a widely recognised framework that illustrates what makes agroecology distinct as a form of food production. In Table 1, we outline how innovation might look different if these elements were used as design principles.

| Element of agroecology | Description | What such a food innovation might look like |

| Diversity | Agroecological systems (e.g., agroforestry, silvopastoral systems, crop-livestock–aquaculture integration and polycultures) optimise the diversity of species and genetic resources in different ways and contribute to a range of production, socio-economic, nutritional and environmental benefits | Diverse, bioregional products like plant protein alternatives, plant milks and cheeses designed as additions, not substitutions, complementing animal products. Products utilising and creating demand for agrobiodiversity e.g. underutilised crops, polyculture harvests, upcycled by-products. Flexible base recipes adaptable to local contexts, resulting in rich bioregional diversity. (See also [5] Recycling, [6] Resilience, [10] Circular and solidarity economy) |

| Co-creation & sharing of knowledge and practices, science and innovation | Agroecology depends on context-specific knowledge to respond to local challenges. Farmer knowledge plays a central role in the process of developing and implementing agroecological innovations. Through a process of co-creation, agroecology blends the traditional, indigenous, practical and local knowledge of producers with global scientific knowledge. | Collaborative R&D with farmers, cooks and eaters based on shared priorities and interests. Open-source innovation with minimal corporate control e.g. bioregional microbial strain banks or distributed networks sharing strains, enzymes, equipment and processes. (See also [7] Human & social value, [8] Culture & food traditions, [9] Responsible governance) |

| Synergies | Agroecological systems create synergies between the diverse components of farms and agricultural landscapes, supporting production and multiple ecosystem services. | Food system design embedding synergies e.g. industrial symbiosis for upcycling, design innovations around whole agroecosystems rather than single crops. (See also [4] Efficiency, [5] Recycling) |

| Efficiency | By optimising the use of natural resources, agroecology produces more using fewer external resources, reducing costs and negative environmental impacts. | Upcycled food by-products generating more food per hectare. Low-tech, decentralised processing reducing energy and transport needs. (See also [1] Diversity, [5] Recycling, [6] Resilience, [10] Circular & solidarity economy) |

| Recycling | By imitating natural ecosystems, agroecological practices support biological processes that drive the recycling of nutrients, biomass and water within production systems, reducing economic and environmental costs. | Upcycling utilising food by-products, unlocking new flavours, umamifying plant foods and diversifying agroecosystem design through full use of crops and animal products. Innovation responding to future agroecological by-product streams e.g. more plant-milk by-products, fewer factory-farmed animal by-products. (See also [1] Diversity, [4] Efficiency, [6] Resilience, [10] Circular & solidarity economy) |

| Resilience | Harnessing diversity, agroecological systems enhance the resilience of people, communities and ecosystems | Design around resilient ingredients, upcycled by-products and agroecosystem designs. Low-tech fermentation and other innovations producing shelf-stable products from surpluses. Open-source knowledge-sharing facilitating adaptations of techniques to local and regional conditions and empowering community resourcefulness, self-sufficiency and interdependence. (See also [1] Diversity, [4] Efficiency, [5] Recycling) |

| Human & social value | Agroecology is founded on the principles of dignity, equity, inclusion and justice, all contributing to sustainable livelihoods. It is a people-focused approach that puts the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems. | People-led approaches to innovation with equitable and just decision-making and minimal corporate control. Innovation and R&D processes beginning with people’s needs and desires, rather than mere technological capability or corporate interests. (See also [2] Co-creation, [8] Culture & traditions, [9] Governance) |

| Culture & food traditions | By supporting healthy, diversified and culturally appropriate diets, agroecology values local food heritage and culture, contributing to food security and nutrition while maintaining ecosystem health. | Food culture-led innovation underpinned by flexible base innovations adaptable to different contexts, enriching diverse food cultures. (See also [2] Co-creation, [7] Human & social value) |

| Responsible governance | Transparent, accountable and inclusive governance mechanisms at different scales are necessary to create an enabling environment that supports producers to transform their systems. | Contextual regulatory parameters for evaluating alignment of innovations with agroecology and public goods. Inclusion of community members in governance processes regulating innovation to ensure public interests shape the innovation landscape. (See also [1] Diversity, [2] Co-creation, [7] Human & social value) |

| Circular & solidarity economy | Agroecology seeks to reconnect producers and consumers through a circular and solidarity economy that prioritises local markets and supports territorial development. | Upcycling food by-products complementing other practices like composting and biomaterials, with the best solutions depending on context. Fermentation and other culinary techniques unlocking new sources of value for agroecological systems, producers, and consumers, building on traditional knowledge. (See also [1] Diversity, [4] Efficiency, [5] Recycling, [6] Resilience) |

If innovation were aligned with agroecological principles as outlined in Table 1, it could, for example, help address the possible future ‘protein gap’ caused by reduced meat consumption discussed earlier. Processes like fermentation, umamification and upcycling offer ways for innovation to transform protein-rich agroecological ingredients and their by-products into protein-rich foods that are more appealing to more eaters than legumes alone. Agroecological versions of innovations like cheeses made from fermented plant ingredients, fermented plant meat analogues, and new flavourings derived from microbes like umami-rich condiments are just some examples. These alternatives, alongside approaches to make whole plant foods even more delicious, and less but better meat, can all fit within an agroecological framework whilst enriching rather than impoverishing food cultures. These plant-forward approaches are not one-size-fits-all solutions, nor are they intended to replace all animal products, but are potential additions that, if aligned with agroecological design principles, could make agroecological diets more delicious, inclusive and realistic. And the same is true for many other kinds of food beyond protein.

iii. What is at stake in connecting agroecology and food innovation?

Whilst agroecological solutionism is problematic, we believe the ongoing co-option of agroecology is important to resist. Walthall et al. (2024) identify three forms of co-option: simplification—reducing agroecology to a narrow, apolitical technical practice; false equivalence—treating agroecology as interchangeable with ‘sustainable intensification’ or other less ambitious frameworks; and confusion—deploying its language in ways that obscure or dilute its transformative intent.¹¹

Framing food innovation as agroecological could seem like solutionist co-option. Yet as shown in Table 1, food innovation need not simplify agroecology; rather, it can expand it by linking ecological and cultural dimensions while confronting the trade-offs and potential shortcomings of an agroecological future. It can avoid false equivalence by remaining explicitly oriented toward justice, sovereignty and context. And it can resist confusion if co-created with farmers, communities and food cultures, keeping its transformative purpose clear and allowing new, context-specific food cultures to emerge rather than being imposed from above.

Food innovation doesn’t provide answers for every challenge within agroecological solutionism. The need for tens of millions more agricultural labourers and the resulting unprecedented levels of urban-to-rural migration are just two examples that we need to wrestle with to ground agroecological futures in reality. Yet within this framing, food innovation can become one element in a broader agroecological toolbox that helps move discussions beyond binary solutionist positions and contributes toward the shared goal of a food system that is more just, ecological and flavoursome.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Eliot and Josh conceived this essay together. Eliot wrote the first draft, Josh provided editorial input, and they developed it further together.

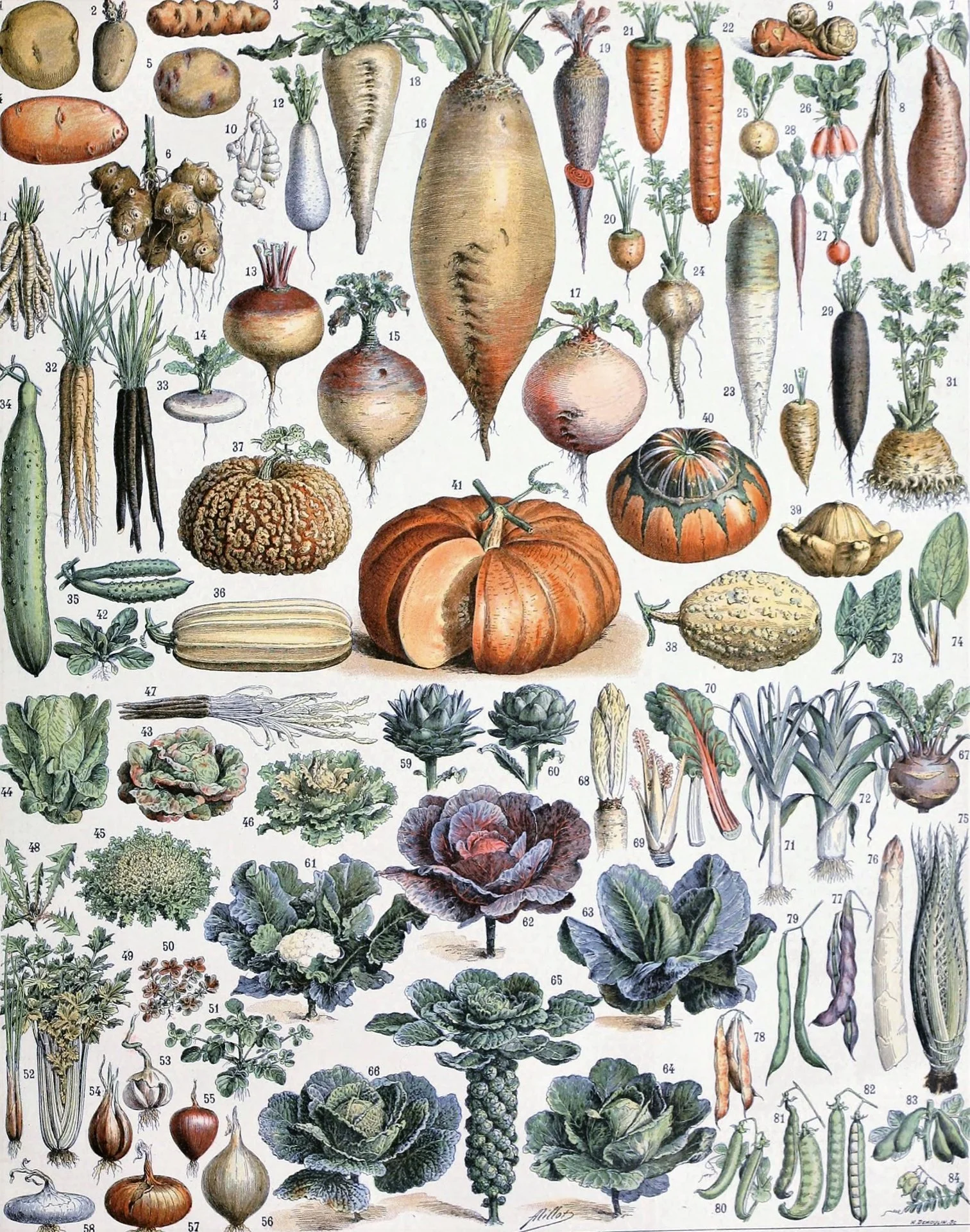

Image credit: Adolphe Millot (1875) Vegetable Illustration.

Endnotes

[1] Julie Guthman (2024), ‘The Problem with Solutions’, University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA; Evgeny Morozov (2013), ‘To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism’, PublicAffairs, New York, USA; Elisabeth Abergel (2024), ‘Dead Meat: Competing Vitalities, Cultivated Meat Imaginaries and Anthropocene Diets’, Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore.

[2] Colin Ray Anderson, Colin Ray, Janneke Bruil, Michael Jahi Chappell, Csilla Kiss, and Michel Patrick Pimbert (2019), ‘From Transition to Domains of Transformation: Getting to Sustainable and Just Food Systems through Agroecology’, Sustainability.

[3] Garrett Broad introduced this term in a BlueSky thread, which he explains further in an episode on Feed: a food system podcast by TABLE, ‘What is food solutionism? And why does it limit us’

[4] Indeed some seem to argue that seemingly limitless ‘regenerative beef’ is possible to produce, though this likely reflects a co-opted version of agroecology; see section iii for more.

[5] Kajsa Resare Sahlin, Line Gordon, Regina Lindborg, Johannes Piipponen, Pierre Van Rysselberge, Julia Rouet-Leduc and Elin Röös (2023), ‘An exploration of biodiversity limits to grazing ruminant milk and meat production’, Nature Sustainability.

[6] Baudish et al. (2024) argue that the ‘protein gap’ cannot be fully understood without also considering disparities in access, equity and power in food systems—the ‘justice gap’—which links directly to agroecological principles of equity, inclusion, and food sovereignty. See: Isabel Baudish, Kajsa Resare Sahlin, Chritophe Béné, Peter Oosterveer, Heleen Prins and Laura Pereira (2024), ‘Power & protein—closing the ‘justice gap’ for food system transformation’, Environmental Research Letters.

[7] Slow Food (2023), ‘Plant The Future’.

[8] Feed: a food system podcast by TABLE, ‘What is food solutionism? And why does it limit us’

[9] A similar method has been used elsewhere: e.g. Chantal Clément and Francesco Ajena (2021), ‘Paths of least resilience: advancing a methodology to assess the sustainability of food system innovations - the case of CRISPR’, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems; Maywa Montenegro de Wit (2022), ‘Can agroecology and CRISPR mix? The politics of complementarity and moving toward technology sovereignty’, Agriculture and Human Values.

[10] Per IPES-Food Panel (2022) ‘The politics of protein: examining claims about livestock, fish, alternative proteins and sustainability’ via Isabel Baudish, Kajsa Resare Sahlin, Chritophe Béné, Peter Oosterveer, Heleen Prins and Laura Pereira (2024) ‘Power & protein—closing the ‘justice gap’ for food system transformation’, Environmental Research Letters.

[11] Beatrice Walthall, José Luis Vicente-Vicente, Jonathan Friedrich, Annette Piorr and Daniel López-García (2024), ‘Complementing or co-opting? Applying an integrative framework to assess the transformative capacity of approaches that make use of the term agroecology’, Environmental Science & Policy.

[12] We acknowledge that we are a research group in a biotech-focused department funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and only occasionally work directly with farmers or food producers. Our perspective is therefore partial. This also comes with responsibility: when discussing connections between agroecology and food innovation, we must recognise the limits of our experience and prioritise the voices, knowledge and goals of those who live and practice agroecology. Our aim is not to prescribe solutions from afar, but based on our own partial perspective and experience to contribute to conversations that support shared values and inclusive, context-sensitive and transformative futures.

[13] ‘What is food solutionism? And why does it limit us’, Feed: a food system podcast by TABLE