What’s in a name?

Table of Contents

i. Naming matters

When working with novel fermentations, particularly those inspired by traditional fermentation practices, choosing how to name what we have made isn’t always straightforward.

Yet names matter. Not for pedantry’s sake, but because, in choosing a name, we are choosing how we would like our fermented food to be received by the world—how we invite people to taste it, use it and understand it, and how it relates to what came before it. And, since everything needs a name anyway, and will be given one by others if not by us, we prefer to be proactive and name things ourselves, and with care.

We see that discourse around novel fermentations seems to happen broadly within a continuum between two poles:

No one culture owns fermentation or specific fermented foods because food culture is fluid and all fermentation practices are the result of cultural exchange.

Specific fermentation practices and products belong to specific cultures, always will, and their appropriation by outsiders is exploitative neo-colonialism.

We get where each of these positions is coming from, and see some truth in both.¹

Food culture is dynamic. None of the traditional fermented foods that are beloved today would exist in their rich and diverse forms (if they even existed at all) without the historic exchange of ingredients, microbes, tools, techniques, ideas, people and cultures across geographies for thousands of years.

And yet, it is problematic when contemporary fermentation practitioners—ourselves included—play too loosely or sloppily with established traditions and cultural knowledge: borrowing from cultures to which they have no ties without doing their homework, removing practices from their original context without giving due credit (or more), even fetishising a caricature of the original culture or simply claiming them as their own invention—all to their own benefit.² This is particularly so when those traditions have historically been marginalised, ridiculed or suppressed, through colonialism or other means, only to become cool and a e s t h e t i c and profitable once adopted by those with greater privilege, power and/or social capital.

What we choose to call our fermented food products is one small but significant way to counter the risk of misrepresenting, diluting, or unintentionally appropriating established food traditions. Well-chosen names carry humility and respect, acknowledging that what we are doing is part of a longer, older lineage by crediting those histories and traditions. In this essay, we explore how we might go about naming novel fermentations sensitively. We include some examples: kōji, to demonstrate how terminological looseness can accompany wider adoption; ‘noji’, to illustrate some of the tensions that arise when naming something novel inspired by multiple distinct traditions; and garum, to explore how the historic nuances of terms can be lost during popularisation. We discuss these examples not to criticise anyone involved in these projects, many of whom are colleagues and friends, but rather to show just how difficult naming well can be, to illustrate what we see as some of the tradeoffs involved, and to suggest some ways to cultivate practices of naming sensitively.

ii. On kōji

Kōji is something of a poster child in contemporary fermentation.³ Its story stretches back thousands of years to China, where it was known as qu (曲; pronounced ‘chew’), and the ancestors of many contemporary East Asian fermentation traditions were known as jiangs (醬).⁴ These early qu starters were probably microbially diverse, spontaneous fermentations, and some contemporary Chinese solid-state fermentation starters—still known as qu—likely resemble these ancestral forms of qu more closely than modern kōji. As these practices were adopted and adapted in Japan, giving rise to the use of specific pure cultures of Aspergillus oryzae, A. sojae, and others, they led to beloved fermented foods like miso, shōyu, sake and others.

In Japanese, the term ‘kōji’ (麹) is used in multiple ways. Rather than using the same word to refer to its multiple forms, as has become common in English, ‘kōji’ is instead modulated depending on its form. ‘Tane kōji’ (種麹) refers specifically to the spores, ‘kōji kin’ (麹菌) refers to the fungus itself, and just ‘kōji’ refers to the fungus grown on a substrate. Additionally, in Japanese, ‘kōji’ can involve a much broader set of microbes—not just Aspergillus spp. but also Rhizopus spp., Monascus spp., Mucor spp., and Absidia spp.⁵

In English, ‘kōji’ is used less precisely, with the term used interchangeably to refer to either the microorganism (usually Aspergillus oryzae, sometimes other Aspergillus spp.), its spores, or the fungus grown on a substrate, usually rice or barley. At times, it can be a little confusing which form of the fungus is being referred to in English.⁶ More often than not, if someone just uses the term ‘kōji’ or ‘koji’ in English without further qualification, they are probably referring to A. oryzae grown on rice. This makes the current common English usage both more broad and more narrow than the Japanese—more broad in that it refers to spores, fungus, and ingredients, and more narrow in that it just refers to A. oryzae (and sometimes other Aspergillus spp.), and not any of the other food-related fungi in Japan. This terminological looseness, in part, coincides with the explosion in kōji’s popularity outside of Japan associated with the current global fermentation renaissance⁷, where it has been used to ferment all sorts of novel substrates for all sorts of novel applications. Indeed, kōji is central to our and others’ work on umamification and flavour production.

This terminological looseness, in part,

coincides with the explosion in kōji’s popularity

outside of Japan

When writing, we choose to use the spelling ‘kōji’, with the longer ‘o’ sound that reflects how it is pronounced and written in Japanese, as opposed to ‘koji’, with a short ‘o’ sound. We choose to do so to prioritise the specificity of the Japanese terminology of ‘kōji’. Yet, we don’t always pronounce it so when speaking aloud, as it often flows more smoothly with English prosody to use a short ‘o’. We also rarely modulate it to ‘tane kōji’ or ‘kōji kin’, instead preferring the more legible (in English) ‘koji spores’ and ‘koji fungus’ (or specifying the exact species). This is one way we try to cultivate the middle ground we introduced earlier, in a way that we feel signifies that kōji has Japanese origins and traditions that should be respected, but not to the extent that kōji is only, and only ever can be, Japanese.

Since kōji is now used for many exciting non-traditional uses, what should be called kōji? We find it makes sense to prioritise kōji’s cultural and technical context here, so any time a fungus traditionally associated with kōji in Japan (not just Aspergillus spp.)is grown on a substrate sufficiently analogous to traditional ones (i.e. grains or legumes) to transform it, and which is often then used to transform another substrate upon which the fungus was not directly grown, then we call this kōji. For this reason, when we grow kōji spores on a substrate other than grains or legumes, and when that product we don’t use for further transformation of other things, we choose to call it another way. An example is our ‘kōji’d lemon skins’, which we called this way instead of ‘lemon skin kōji’, to better indicate how it is made and for what. Likewise, if kōji spores are grown on other substrates like meat or vegetables to break them down and be used directly as an ingredient⁸, then we choose not to use the name e.g ‘beef kōji’ to describe beef with kōji grown on it. A small difference perhaps, but we feel it helps to preserve the cultural and technical context of kōji while still giving license to explore all sorts of novel applications, and feels more precise in describing the different products’ processes and goals.

iii. On noji

Our discussion of kōji illustrates how names can blur as they are adopted across contexts. Another example offers a related but distinct case: naming novel fermentations with links to multiple cultural and microbial lineages.

Neurospora intermedia is a filamentous fungus traditionally used in Java, Indonesia, to ferment okara⁹ (the solid by-product of making soy milk or tofu) to make oncom merah, or red oncom, a protein-rich food.¹⁰ Red oncom is a wonderful example of traditional ‘upcycling’.¹¹ More recently, N. intermedia has been shown to grow well on a wide range of food by-product substrates¹², with tantalising implications for diverse, bioregional fermented protein products made from plant food by-products inspired by these traditional practices.

Beyond protein production, chefs and researchers are experimenting with novel applications for N. intermedia. In one example, a research team led by Vayu Hill-Maini and Jay Keasling collaborated with Alchemist Restaurant in Copenhagen (including our own Nabila), to grow N. intermedia on rice, much like A. oryzae (and other microbes) are grown on rice (and other substrates) as kōji. It thrived, and was used to make a sweet ‘amazake’-like dessert, with a unique sensory profile and bright orange colour.¹³ The creators dubbed the N. intermedia grown on rice ‘noji’, as a nod to its analogy to kōji production.

On the one hand, we love this choice. It feels wry and slightly self-deprecating, while concisely capturing the idea that this product is like kōji, but also different in that it contains microbes other than those typically found in kōji.¹⁴ The name serves as a useful shorthand that is legible within Western culinary circles, where kōji is now widely recognised, and signals its intended use: in this case, ‘amazake’ production.

We also wonder if there is more to the story.

Ragi refers to a cluster of traditional Indonesian starter cultures typically grown on glutinous rice, other grains or cassava, that are used to make different fermented foods, including oncom (based on ragi oncom) and a sweet, fermented, slightly alcoholic dessert called tape ketan (based on ragi tapai).¹⁵ In general, ragi contains diverse microbiomes, and ragi tapai is no exception, with a microbiome usually including the filamentous fungi Amylomyces spp., Rhizopus spp. and Mucor spp. and yeasts like Saccharomyces spp. and Endomycopsis spp. Little known outside of Indonesia, ragi is sometimes referred to as ‘Indonesian kōji’ in the English-language literature.¹⁶

Since a traditional, sweet, fermented dessert (tape ketan) made with filamentous fungi grown on rice (ragi tapai) already exists in the one country where N. intermedia has a documented history of use as human food (Indonesia), might it have made sense for that tradition to serve as the baseline for naming ‘noji’, rather than Japanese kōji and amazake?

We raise this question not to criticise the creators of ‘noji’—as we said, we love the name, and we think we understand why they went with it over one based on ragi—but to illustrate just how complex and potentially fraught naming can be, and the kind of tradeoffs involved.

In many ways, the choice of ‘noji’ is understandable. Although kōji does not typically contain N. intermedia, neither does the ragi used to make tape ketan (ragi tapai).¹⁷ Moreover, kōji is far better known than ragi outside of Indonesia, so using the former as a reference point for naming if one wants to prioritise broad legibility makes sense. Ragi is also often made with additional spices and fruits in the substrate, rather than just grains, and is usually a spontaneous fermentation starter—closer to qu than either kōji or noji. From this perspective, the ‘noji amazake’ arguably does share more in common with kōji/amazake than it does with ragi/tape ketan, making the name a reasonable fit.

At the same time, N. intermedia only has documented traditional use in Indonesia, and other forms of ragi, like that used to make red oncom (ragi oncom), do contain N. intermedia, even if ragi tapai doesn’t. So, using kōji as the naming reference point raises questions about whether the food culture being highlighted by the name is the most appropriate one historically and geographically. If kōji has been called Japan’s ‘national microbe’¹⁸, could N. intermedia be considered, in some sense, (one of) Indonesia’s? Particularly given the fraught history of Japanese colonialism throughout East and Southeast Asia, including in Indonesia, and the tendency in Western food culture to valorise Japan above other Asian countries, using a name rooted in Indonesia could have been an opportunity to acknowledge and intervene in these complex histories and sociocultural dynamics. And as above with kōji, wishing to honour roots does not necessarily entail restricting use. Just as A. oryzae needn’t only be thought of as something that can only ever be Japanese, nor need N. intermedia be categorically viewed as only ever Indonesian—even if that is where these traditions seem to have emerged.

Given that kōji is far better known than ragi outside of Indonesia, it makes sense as a reference point for naming

if one wants to prioritise broad legibility.

We see the main tradeoff here as the one between broad legibility and cultural accuracy. As outlined above, we understand why kōji was selected as the naming baseline. In this instance, we ourselves might have prioritised ragi and tapai ketan as the naming baselines, for multiple reasons: Indonesia is the only place with a culinary history of using N. intermedia; there are already similar traditions of growing N. intermedia on starchy substrates also called ragi (though ragi oncom not ragi tapai); there is already a tradition of fermented rice desserts (tapai ketan); and because we think Indonesian cuisine is deserving of far more celebration and recognition, and Japan seems to be doing fairly well in that department (make no mistake, we are also fans). Perhaps ragi might even be modulated in a fun way like noji, though of course this makes less immediate sense for something less well known!

iv. On garums

Kōji and noji illustrate naming tradeoffs as living traditions are adapted. Another example presents a different challenge: when few extant analogues remain, but the revival and reinvention of an ancient category has produced a contemporary name whose meaning has drifted far from its historical roots.¹⁹

The name ‘garum’ is a source of much confusion. Originally, ‘garum’ referred to a class of fermented/autolysed fish condiments²⁰, with Greek and North African roots, later popularised by the Roman Empire.²¹ These sauces were made using the whole fish, guts and all, chopped up, salted and placed in an outdoor covered vat for many months, with enzymes from the guts breaking down the flesh in a process of autolysis to produce a salty, dark-coloured, umami-rich liquid condiment.

In contemporary gastronomy, the term ‘garum’ has since been redefined and popularised by Noma to refer to a much more loosely related collection of salty, dark-coloured, umami-rich liquid condiments.²² These novel ‘garums’ are made with all sorts of substrates, replacing fish with other animals or even with fungi or plants. They are also made differently. Whereas in ancient garums, the enzymes were endogenous to the substrate (the enzymes came from the fish guts), in most novel ‘garums’, these are replaced with exogenous sources of enzymes (coming from outside the main substrate), like kōji. Many novel ‘garums’ we see tend to follow the Noma protocol, salted anywhere between 4-18% and kept at 60℃ for 10-12 weeks to speed up the process (an understandable goal, particularly in a restaurant context), whereas ancient garums were typically aged outside at ambient temperature for 6 months to a year or more.²³

At what point is a garum not a garum?

Table 1 shows some of the various types of novel ‘garums’ and how they differ from the ancient garums from which their name derives.

| What is the primary substrate? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | Other animal products | Fungi or plants | ||

| What is the source of enzymes? | ||||

| Only endogenous enzymes | Ancient garum, Colatura di Alici, nam pla+, nước mắm+, shottsuru+, Worcestershire sauce+ | Rose and shrimp garum* | ||

| Enzymes from other exogenous sources (like kōji, industrial enzymes) | Uobishio+, koji-chovies+ | Ptarmigan garum; beef garum*, roasted chicken wing garum*, grasshopper garum*, moth larvae garum*, pig’s blood garum*, shishibishio+, various jiangs (usually more paste-like)+ | Yeast garum*, oat milk garum*, smoked pumpkin garum*, sunflower seed milk garum*, pea garum*; theoretical (?) garums made with tropical fruit-derived enzymes*; our bran amino+; shōyu+; kokubishio+, kusabishio+ | |

Table 1: Novel ‘garums’ and their analogues.

Entries denoted with (*) are from either the Noma Guide to Fermentation or @nomacph. Entries denoted with (+) technically fit into each category but are their own traditions and are not typically considered a garum. They are included to further illustrate the ambiguity of the term.

As useful as Noma’s technique is, and as great as it is to see all that it has inspired, the name ‘garum’ now seems to be used quite loosely by fermenters around the world to describe all sorts of products that have little in common with ancient garums, aside from being a similarly coloured, salty, and (sometimes but not always) umami liquid condiment. Many contemporary ‘garums’ are made using a different process, a different source of enzymes, and with different ingredients from ancient garums. Though we presume this was never Noma’s intention, it has nonetheless resulted in a whole class of novel ferments that are perhaps not ideally named. Maybe this is fine, but we have a hunch that more may be lost from this looseness than gained: namely specificity, an attention to differences in process, and a reduction in real diversity and a foreclosing of potential diversity.

At what point is a garum not a garum? We would say that many of these so-called garums, specifically those made with kōji, have more in common with traditional East and Southeast Asian fermentation categories, some that are still in existence and others that have since evolved. As noted earlier, all kōji-based fermented products originated in China, where they were (and still are) known as jiangs. Once adopted in Japan, they became known as hishio (醤) and were further categorised depending on their primary substrate, including uobishio (魚醤, fish-based), shishibishio (肉醤, meat-based), kusabishio (草醤, vegetable-based) and kokubishio (穀醤, grain-based ferments).²⁴ The products in each of these categories were hugely diverse (that diversity is barely described in English, and likely much of it is lost to time) and evolved many times over many centuries.

Kokubishio, for example, over time evolved into many of the modern fermentation categories familiar today, like shōyus and misos. The ‘garums’ made with plant substrates and kōji shown in Table 1—such as oat milk or pea garum—are closer to shōyu than to any ancient garum.²⁵ The main difference when compared to a traditional shōyu is that they use non-traditional plant substrates (e.g. oat milk okara or peas) and are aged/fermented at higher temperatures for shorter periods.²⁶ Despite these differences, the plant ‘garums’ are closer to a shōyu than any ancient garum, which were also fermented for longer at ambient temperature and made with neither kōji nor plant substrates.

The ‘garums’ made with meat very closely resemble products in the historic category shishibishio, which existed for many centuries and were made with meat, kōji and salt. Shishibishio doesn’t really exist as a modern fermentation category, as such, nor does it have any famous derivatives comparable to how shōyu derived from kokubishio, aside from a few regional or revived forms in parts of Japan.²⁷ The primary difference between shishibishio and meat ‘garums’ is the latter’s hotter, shorter process, but otherwise, they are very similar, and closer to one another than either is to ancient garums.

To be clear, we’re not suggesting that all kōji-based ferments should therefore instead be referred to as jiangs or subcategories of hishio like shishibishio. That would logically also require renaming the likes of miso and shōyu, replacing them with now redundant categories from which they evolved, which doesn’t make sense: they are now their own things with their own names. Nevertheless, we raise this point because many of the products within the nebulous contemporary category called ‘garums’ have far more in common with these various lineages of East and Southeast Asian fermentations than they do with ancient garums, such that these East and Southeast Asian lineages might have been a more suitable starting point for naming than garum. In the case of shōyu and miso, these renamings happened gradually within the same culture, tracking gradual changes in ingredients, process, and sensory profile, whereas now we're dealing with rapid, discontinuous, globalised shifts in all three and their namings—which we think invites us to consider some guidelines for naming sensitively.

So what might we have called this contemporary type of garum instead? Broadly speaking, we find the most appropriate naming baselines follow whenever possible the main ingredients and closest existing culinary category. If a salty, dark, umami-rich liquid condiment is made with grains and/or legumes (or their by-products) and kōji, then shōyu seems to us the most appropriate reference point—even if certain process details deviate somewhat from what is traditional, like fermenting/ageing at higher temperatures.

For meat-based products made with kōji, the answer is less clear-cut. There isn’t a widely recognised extant category that neatly fits. If one wanted to prioritise composition and technical cultural correctness, the archaic term ‘shishibishio’ could serve as a baseline (and it does delightfully roll off the tongue in a way few words do). But if the priority is broad legibility, then we see using the word garum as more understandable given its popular momentum—especially as the originating culture, in this case ancient Rome, is extinct, which maybe makes it more permissible to be a bit loose with naming.

Another option is the more culture-neutral term ‘liquid amino’, which Rich Shih and Jeremy Umansky use in their wonderful book ‘Koji Alchemy’.²⁸ We adopted this reference when naming our ‘bran amino’, since that product has no connection to historic garums, is made using industrially produced exogenous enzymes rather than with guts or even kōji, and is not even fermented—and therefore, in our minds, is not a shōyu even if it’s made with the by-product of a plant. While this more modernist approach that seeks to name without any reference to existing cultures made sense for us in this case, in general we prefer more culturally situated names whenever possible. Depending on how others navigate these tradeoffs, other approaches may make more sense.

v. Some strategies for naming sensitively

These examples show some of the tradeoffs with naming novel fermentations—for example, between fidelity to historical/cultural origins, legibility to a new context, or a more universalising neutrality—and that the choices involved—both the available ones and the ‘right’ ones—aren’t always obvious. However, when we have made a novel fermented food, and are unsure what to call it but know we would like to try to name it sensitively, we find a useful starting point is to reflect on the following questions:

About the fermentation itself:

What is the desired flavour profile and intended use?

What ingredients does it use, and what functional properties do they bring?

Which microbes are involved?

What process or method does it involve?

About the fermentation in relation to existing traditions:

Are there any historical or contemporary analogues—well-known or otherwise—to it?

Is the combination of process, ingredients, microbes and flavour profile sufficiently similar to an existing product to merit using the latter as a naming ‘baseline’, or is it distinct enough to merit a new category entirely?

Does it feel more appropriate to refer to an existing baseline, or to seek a more neutral, culture-independent name?

If a baseline exists, in which culture(s) did this product/practice originate?

If it relates to multiple traditions with unclear origins, is it closer to one than another?

Where did we learn about this style, from whom and in what context?

What is our relationship to the existing tradition: are we custodians, borrowers, something in between or something else?

Here is an example of how these questions have helped guide us toward what we hope are sensitive naming practices, emerging out of some of our recent R&D. We’ve fermented pumpkin by-products like skin, seeds and/or guts using kōji in different ways. If we were to add additional protein (i.e. TVP) and salt to the mix and ferment it for months to make a relatively thick, umami-rich paste, then this product should probably be considered a miso. If we add water as well, it would make sense to call it a shōyu. If we keep the water but don’t add salt or additional proteinous substrate, the mixture would be very carbohydrate-heavy, likely resulting in a sweeter product that might be best described as an amazake.

Sometimes naming sensitively can be as simple as showing one is considering the necessity of doing so. We’ve R&D’d products that are heavily inspired by existing traditions but due to the addition of a novel ingredient or process, are sufficiently different that we feel its important to subtly indicate this by slightly modulating the name—for example with quotation marks, as with our spent tea ‘saag’ and fruit presscake ‘marzipan’, or with approximating suffixes like our cauliflower XO-ish.

Other cases will be more complex, with no obviously correct answer. For example, many traditions of spontaneous solid-state fermentation starters made with grain and legume substrates exist across the world, including qu, nuruk, meju, namako and the aforementioned ragi.²⁹ If we were to create an analogous spontaneous starter using a novel substrate like a perennial grain, which of these related practices should be considered the baseline from which it is to be named? It could conceivably be equally as related to multiple traditions; the ‘right’ answer might lie in some of the subtler details—both the more technical/practical ones like the exact type of substrate, the ratios of the ingredients, the preparation, the form, and the eventual use, as well as the more cultural/identity-based ones like one’s own heritage, where one lives now, and the cultural context one wishes to relate to through one’s fermentation practice. At some point it may require a judgment call, and indeed this very question is one we have been recently grappling with for a larger project on these products.

Rather than trying to find infallible ‘correctness’ in every case, which sounds like a recipe for paranoia if it would even be possible, we would like to support an approach that values this searching, weighing, learning process as an end in itself. Overall, while more diligent naming won’t solve every ethical or cultural question surrounding novel fermentations, we think it helps to set the tone in a way that signals humility, awareness and respect to an ancient, broad and interconnected continuum of practices. We also suspect it might help find names that feel sensitive, and will hopefully help members of their originating cultures feel respected, while also allowing innovation, creativity and exchange to flourish—for us, the ultimate dual goal.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Eliot and Josh conceived this essay together. Eliot wrote the first draft, Josh provided editorial input, and they developed it further together. Thanks to Kim and Kevin Qiu for fruitful discussions that helped inform the piece.

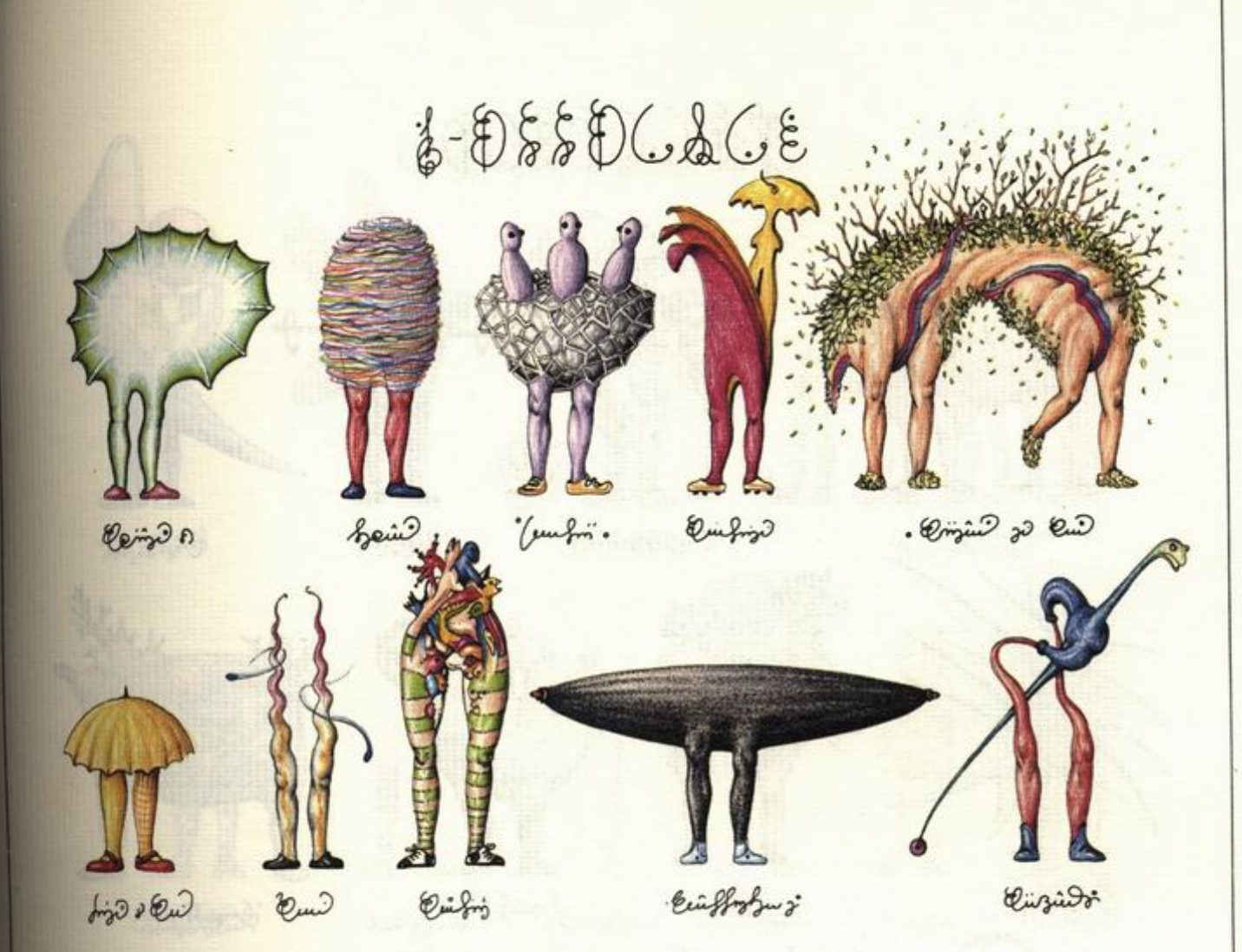

The header image is taken from the delightfully strange Codex Seraphinianus (Luigi Serafini, 1981).

Endnotes

[1] A couple of Instagram posts & comments sections we thought well captured some of the grey area between these extremes were here and here.

[2] Miin Chan (2021), ‘Lost in the brine’, Eater.

[3] For a primer on kōji, see Koji - history and process, Nordic Food Lab.

[4] William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi (2021) ‘History of koji - grains and/or soybeans enrobed with a mold culture (300 BCE to 2021)’, Soyinfo Center; William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi (1983), The Book of Miso, Ballantine Books: New York, USA.

[5] Ibid.

[6] See also: Maya Hey and Eleni Michael (2025), ‘A Whole New World of Possibilities’: Koji Uses and Ambiguities on the Global Marketplace’, Food, Culture and Society. Here the authors conceptualise different English-language uses of the term ‘kōji’ as ‘kōji-the-spore’, ‘kōji-the-enzymes’ and ‘kōji-the-ingredients’.

[7] While this renaissance is not happening equally everywhere or for the same reasons—it has a geography and a sociology—we note that it is also unfolding in many sites beyond the typical ‘West’, for example Central and South America, India, and indeed Japan.

[8] Rich Shih and Jeremy Umansky (2020), Koji Alchemy: Rediscovering the magic of mold-based fermentation, Chelsea Green Publishing: London, UK.

[9] Okara is another example of a Japanese loan word to English. It is known by other names in other Asian countries where it has long been produced, including dòuzhā or dòufuzhā in China, biji or kongbiji in Korea, and ampas tahu in Indonesian.

[10] Oncom hitam, or black oncom, is a related traditional Indonesian ferment typically made with peanut presscake and with a different, more diverse microbiome typically dominated by Rhizopus spp., the same family of microbes used to make tempeh. We choose to refer to oncom as red/black oncom rather than oncom merah/hitam for the same reasons we refer to ‘kōji spores’ instead of ‘tane kōji’. Notably, oncom is one of the only traditional East and Southeast Asian ferments that does not originate in China. See: Vayu Maini Rekdal et al. (2024), ‘Neurospora intermedia from a traditional fermented food enables waste-to-food conversion’, Nature Microbiology.

[11] Though it is not known as upcycled food, simply as food. Indeed this could be seen as sign of success for a given food or by-product. We hope all upcycling might one day reach such a point.

[12] Vayu Maini Rekdal et al. (2024), ‘Neurospora intermedia from a traditional fermented food enables waste-to-food conversion’, Nature Microbiology.

[13] Vayu Maini Rekdal et al. (2024) ‘From lab to table: Expanding gastronomic possibilities with fermentation using the edible fungus Neurospora intermedia’, International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science.

[14] Although, by its broadest definition in Japanese (a fungus grown on rice for food), noji could conceivably just be called kōji, and it would be technically correct (though not culturally, since there is no traditional practice that we know of of using Neurospora in Japan).

[15] When it is even referred to at all. We haven’t found a great deal of recent literature on ragi tapai in English. See some examples: Indrawati Gandjar (2003) ‘Tapai from cassava and cereals’, Symposium and Workshop on Insight into the World of Indigenous Fermented Foods for Technology Development and Food Safety; S.D. Ko (1986) ‘Indonesian fermented foods not based on soybeans’, in: C.W. Hesseltine and H.L. Wang (eds) ‘Indigenous fermented food of non-western origin’, Mycologia Memori Vol. 11.; M. J. Robert Nout and Kofi Aidoo (2010) ‘Asian Fungal Fermented Food’, Industrial Applications.

[16] Ibid.

[17] S Siebenhandl, Lydia Lestario, D Trimmel, Emmerich Berghofer (2001), ‘Studies on tape ketan - an Indonesian fermented rice food’, International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition.

[18] As declared by the Brewing Society of Japan. See also Victoria Lee (2021), The Arts of the Microbial World: Fermentation Science in Twentieth-Century Japan, University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA.

[19] We do not necessarily think this is a problem in itself—indeed it happens a lot that the referents of words drift over time. It may not be ideal specifically when this phenomenon forces us to give up useful precision—which we would argue is the case here with garum.

[20] Throughout we will refer to this original ‘baseline’ garum as ‘ancient garum’, for clarity.

[21] The term ‘garum’, even in ancient times, refers to a diverse array of fish-based sauces rather than a single product. For more on the contested history of ancient garums, see: Sally Grainger (2021), ‘The Story of Garum: Roman Fish Sauce in a Modern Context’, Fermentology; Sally Grainger (2021), Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted Fish in the Ancient World, Routledge: Abingdon, UK

[22] René Redzepi and David Zilber (2018), Noma Guide to Fermentation, Artisan: New York, USA; Emile Samson, Taeko Hamada, Clara Onieva Martín, Nabila Rodríguez Valeron, Carlos Suárez, Sara Vande Velde, Anna Verlinde and Josh Evans (2025) ‘Old Foods, New Forms: A framework for conceptualising the diversification of traditional products through gastronomic innovation’, International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science.

[23] René Redzepi and David Zilber (2018), Noma Guide to Fermentation, Artisan: New York, USA.

[24] William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi (2004), ‘History of Soy Sauce, Shoyu, and Tamari’, Soy Info Centre; Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (2023), ‘An introduction to Japanese Fermented Foods’.

[25] And possibly even closer to other forgotten forms of kokubishio or kusabishio.

[26] We note the methodological differences in how Noma produce ‘garums’ vs ‘shōyus’. Both are made with kōji, but the latter is done so at a lower temperature for longer and the kōji is grown directly on the primary substrate, rather than added with a separate substrate. The Noma Guide to Fermentation section on shōyu (p.337) does note that ‘some of these recipes don’t fit snugly into shōyu; some have just as much in common with garums. We continue to call them shōyus because unlike garums they don’t contain any animal flesh.’ We note in Table 1 however that Noma has also produced many ‘garums’ with no animal products at all. These examples illustrate how difficult it can be to name new products, and how often one must adjudicate between different priorities in decide among multiple possible options.

[27] See Nguyen Hien Trang, Ken-Ichiro Shimada, Mitsuo Sekikawa, Tomotada Ono and Masayuki Mikami (2005), ‘Fermentation of meat with koji and commercial enzymes, and properties of its extract’, Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. For some discussion on and example recipes for shishibishio see here and here (in Japanese). For example products see here (notably marketed as a ‘pork garum’ despite being made in Japan—possibly linked to the European name of the company?) and here (in Japanese).

[28] Rich Shih and Jeremy Umansky (2020), Koji Alchemy: Rediscovering the magic of mold-based fermentation, Chelsea Green Publishing: London, UK.

[29] Jyoti Tamang, Koichi Watanabe and Wilhelm H Holzapfel (2016), ‘Review: Diversity of microorganisms in global fermented foods and beverages’, Frontiers in Microbiology.