Waste bread shio kōji

This is part of our series on upcycling bread by-products.

Table of Contents

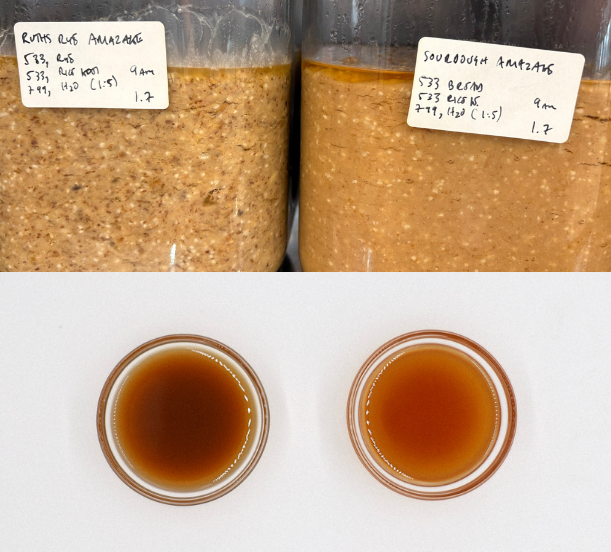

Artisan sourdough (top) and rye (bottom) bread shio kōji.

Though they look almost identical, they have quite distinct flavour profiles.

i. Introduction

Shio kōji is a Japanese umami seasoning made by fermenting kōji, salt and water. It is often sold as a strained and sometimes clarified liquid, but can also be used as a porridge-like slurry. In either form, it is widely used as a marinade to tenderise and enhance the flavour of meat, fish and vegetables, adding umami, richness and depth to (and drawing them out from) the raw ingredients.¹

In this version, we take a slightly different approach to a traditional shio kōji, growing the Aspergillus oryzae on waste bread instead of grains, harnessing its ability as an enzymatic powerhouse to digest residual proteins and carbohydrates within the bread and unlock a range of umami-rich flavour compounds.

We tried making this recipe with various breads, including artisanal sourdough and rye breads and more industrial sliced white and rye breads, to observe how the A. oryzae grew on the different substrates. It works for any kind of bread, though it does taste quite different depending on which you use, and requires some tweaks if you plan to use very processed industrial white bread (see the ‘Adaptations’ section for more details). We particularly liked shio kōji made with artisanal rye bread and artisanal sourdough, both of which were complex, toasty and umami-rich, with some bready sweetness.

Growing kōji on stale rye bread.

ii. Recipe

Ingredients

Stale bread, cut into uniform 2cm pieces

Aspergillus oryzae spores, 0.2% by weight²

Water, equal to the weight of the finished kōji

Salt, non-iodised, 5% by mass of previous ingredients minus salt content of the bread³

Method

Steam the stale bread in a Rational oven on full steam setting at fan speed 3 for 5 minutes. Remove the steamed bread from the oven and allow it to cool to 35°C.⁴

Inoculate the cooled bread with the kōji spores, mixing with gloved hands to evenly distribute them. Before inoculating, ensure all tools, surfaces and hands are sterilised to prevent contamination. Wrap the inoculated mixture in a moist muslin cloth that has been pre-boiled and wrung out. Ferment in a climate-controlled fermentation chamber at 32°C with 70% relative humidity for 24 hours, allowing the kōji to grow.

Remove the trays from the fermentation chamber and, with gloved hands, carefully lift the muslin package and flip it over. Spray the muslin cloth with a little water to re-moisten it and prevent it from drying out. Repeat this process after an additional 12 hours (36 hours total) to help ensure consistent kōji growth.

When the bread kōji has finished growing, after a total of 42 hours in our case⁵, remove it from the oven or fermentation chamber and reweigh it. Combine it with an equal weight of water and 5% salt (based on the total weight of bread kōji and water).

Sterilise a large fermentation vessel using alcohol or boiling water. Allow to evaporate if the former, and to cool if the latter. Pour in the bread kōji–brine mixture and cover the vessel mouth with a fresh, dry muslin cloth.

Ferment at room temperature out of direct sunlight for 7 days, either stirring daily with a sterilised spoon or sealing and gently shaking the vessel to redistribute the solids and liquids.

Once fermentation is complete, strain the mixture through fine muslin cloth or centrifuge to separate the solids. Retain the liquid. The shio kōji can be refrigerated for up to 1 month or frozen for longer storage. Refrigeration and freezing slow down but do not completely stop the microbial and enzymatic activity. For a shelf-stable product, seal the shio kōji in an airtight jar or vacuum bag and heat in a water bath or steam at 90°C for 40 minutes to pasteurise, denature enzymes and arrest further activity.⁶ The shio kōji can be heat-treated if used as a seasoning (still delicious), but not if you intend to use the active enzymes e.g. for a tenderising marinade.

Some of the different bread shio kōjis that we made, before straining.

iii. Adaptations

This recipe works with all sorts of different breads, each of which yields slightly different flavours. We did find that A. oryzae won’t grow well on more processed breads, which contain more additives to enable greater shelf life and inhibit mould growth. To mitigate the effects of these additives when making shio kōji from more industrially processed breads, we added 1 part cooled, steamed rice to 1 part bread to make the kōji growing substrate. The rest of the recipe remains the same.

We used an A. oryzae strain that is usually used to make barley kōji, which we found to work well on different bread substrates with differing levels of whole grain fibre. You could try experimenting with other strains of A. oryzae to see how they impact kōji growth and flavour development in the shio kōji.

A delightfully serendipitous moment once again reminded us how fermented products are dynamic and living. The artisan sourdough shio kōji was delicious right after fermenting for 7 days, but when we dug it out of the freezer a couple of months later for a photoshoot, we found that the flavour had developed even further, giving a remarkably ham-like flavour. Before freezing, we had pasteurised the waste bread shio kōji. Bread shio kōji is rich in amino acids and sugars that, when heated, undergo Maillard reactions, creating rich, savoury, meat-like flavours. Though pasteurisation was originally intended to make the product shelf-stable, it unexpectedly yielded a deeper, meatier profile.⁷ So, if you’re after a particularly meaty bread shio kōji, try pasteurising it. If you’d prefer a shelf-stable product that retains the original toasty, bready flavour profile, use an ultra-high-speed, high-temperature pasteurisation process instead, though this requires specialised equipment.

Since different breads contain varying amounts of residual salt, especially artisan breads, we adjust the added salt accordingly. For artisan loaves, we estimate about 1.4% salt by weight (based on 70% dry matter and 2% salt in the dry portion). To maintain a 5% total salt concentration in the shio kōji, we subtract the estimated salt from the bread before adding more. For most commercial breads, salt content is lower so check the label, or if unknown, assume negligible and add the full 5%. If you happen to know the exact salt percentage of the bread, even better.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Kim performed the original culinary research, with further testing conducted by Nurdin, who documented the process with notes and photography. Eliot wrote the article using these notes and following further discussion with Nurdin and Kim, with contributions and editorial feedback from Josh. Eliot and Nurdin photographed the final product in our food lab.

Related posts

Endnotes

[1] For a more in-depth introduction to shio kōji see: How To Make Shio Koji 塩麹の作り方, Just One Cookbook.

[2] We used an A. oryzae strain that is usually used to make barley kōji, which we found to work well on different bread substrates with differing levels of whole grain fibre.

[3] Shio kōjis can vary in their saltiness. Those with lower salt concentration will ferment more, while those with a higher salt concentration will ferment less and be more stable. This is the salt percentage we like here, but it could be adjusted if desired. To ensure consistent salt concentration in the final product, we standardise salt addition to 5% of the combined weight of bread kōji and water. See the ‘Adaptations’ section for more.

[4] Steaming the bread sterilises it prior to inoculation, which helps to control for unwanted microbial growth during kōji fermentation.

[5] The total kōji growing time may vary if different ovens or setups are used. The turning and remoistening helped with more consistent growth and prevented the kōji from becoming too dry.

[6] You can use a different, more precise pasteurisation method (e.g. 72˚C internal temp for 15 seconds) if you have access to specialist equipment and prefer to do so.

[7] Though we didn’t taste the pasteurised bread shio kōji before freezing, the flavour development is more likely attributable to pasteurisation than to freezing—though fermented products can also continue to evolve even while frozen.