Industrial symbiosis for upcycling

Table of Contents

i. Systemic barriers facing upcycling

We use fermentation and other techniques in our culinary R&D to upcycle food by-products, transforming what might typically be considered inedible into delicious foods. The results are exciting, yet we and many other innovators have found that trying to scale these products beyond the prototype phase and working with by-products in real-world conditions brings significant logistical challenges and risks.

Food by-products are often bulky, wet and/or highly perishable. This makes them difficult to handle and store, expensive to transport over long distances, and makes it essential to immediately process them to make them shelf-stable, e.g. by dehydrating them. Yet many places where by-products are produced, like breweries or mills, do not have the space or infrastructure to do so and often operate on tight margins that make it difficult to integrate additional processes like upcycling into their existing workflows. These challenges can be further compounded by waste handling regulations. In some places, food by-products are legally defined as waste once they leave the production site, rather than as usable ingredients, which then restricts their use.

Attaining by-products of consistent quantity and quality from third-party suppliers can also be challenging.¹ Changes in a supplier’s raw materials, processing methods, or output volumes can quickly disrupt availability, whilst by-product composition may also vary depending on seasonality, where they are sourced from, or how they are processed.

And while some by-products are produced in large volumes at centralised industrial sites, others are produced in smaller quantities across dispersed locations, like those generated on farms or smaller processing facilities. This fragmented supply makes it difficult to develop efficient collection and processing systems or to achieve economies of scale in transportation.

Today, many by-products are inexpensive, or even free, because they hold little value for their producers, who may actually save money by giving them away instead of paying for disposal. Yet their value will likely increase as their potential as food ingredients becomes more widely recognised. In time, a by-product might no longer be considered waste at all. Instead, it could be viewed simply as another ingredient—a positive shift for the food system, but potentially problematic for companies currently dependent on low-cost, stable supplies from third parties.

To realise the full potential of upcycling at scale and in the long term, all of these challenges suggest we may need to fundamentally rethink and redesign the systems through which we grow, produce and process food.

ii. Co-located food production facilities could use one another's side streams

Co-locating food production and processing facilities and designing them to use each other's by-products as inputs is a promising solution rooted in the principles of ‘industrial symbiosis’, a concept from industrial ecology and circular economy.² A well-known example from our home of Denmark is Kalundborg Symbiosis, an industrial park where chemical and materials manufacturers are co-located and designed to use each other's by-products, waste heat and water.

Applying these principles to food production could address the unnecessary wastefulness of the food system. Plant Chicago is one working model, where co-located facilities—a brewery, an aquaculture farm, a mushroom farm and a market garden—circulate resources to produce different types of foods. While designs like this could benefit the food system broadly, we think they hold particular promise for upcycling food by-products.

This approach could overcome many of the barriers mentioned earlier, including reducing:

transportation needs, especially useful for short shelf-life ingredients

energy use, since by-products might not need to be processed to be shelf-stable

supply chain risks, as interdependent operations are all part of the same system, not relying on third parties

regulatory hurdles, because by-products don’t need to be re-classified as waste if they never leave a facility

Beyond solving logistical challenges, this approach could also substantially increase total food yield from the same volume of ingredients or land area.

iii. What a more symbiotic future of upcycling could look like

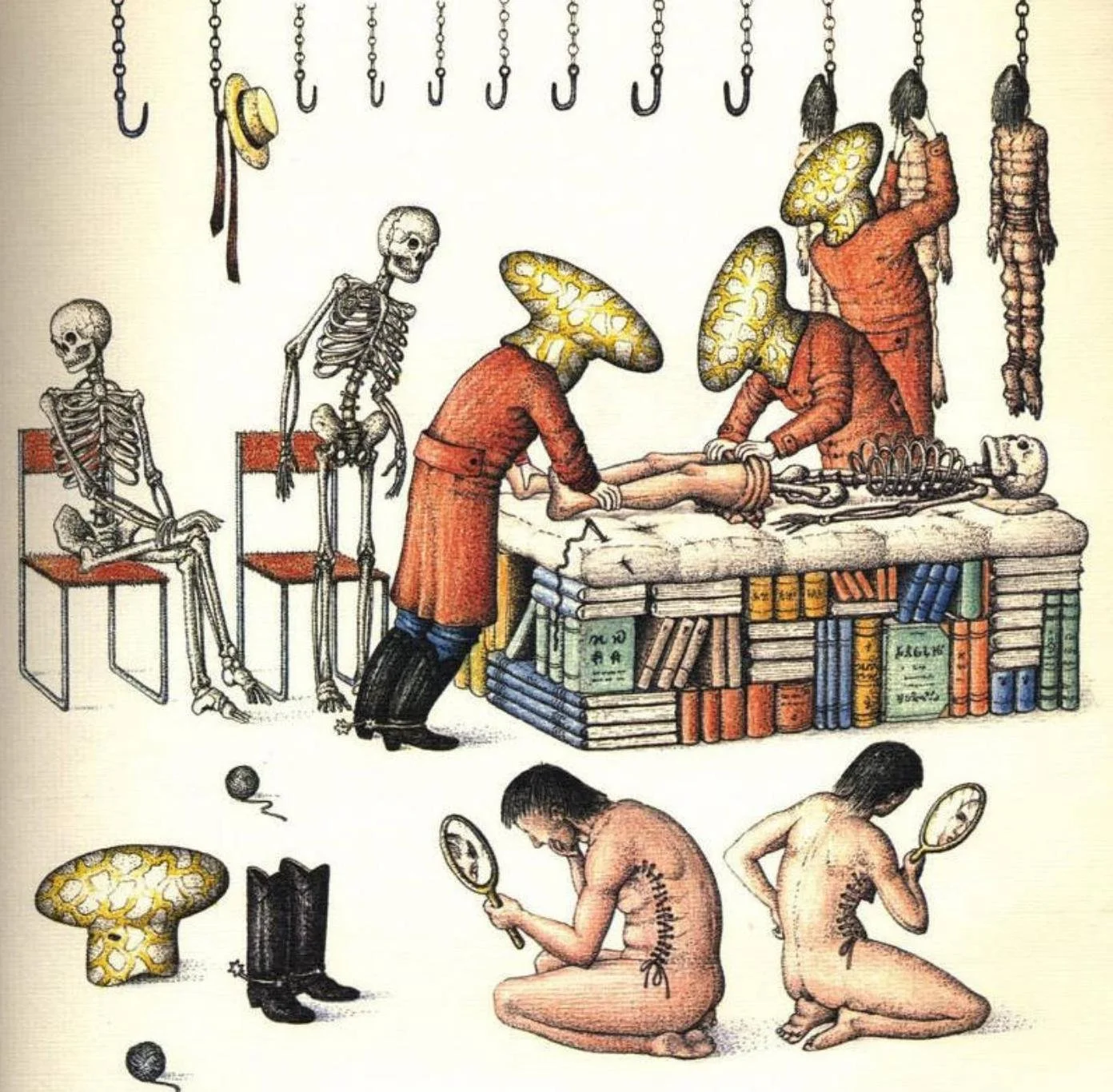

We explore this concept further with one hypothetical system where a mill, a maltery and brewery, a food processing facility³ and a mushroom farm are co-located and designed to use each other's by-products.

Step 1: Perennial grains are grown using agroecological principles in agricultural fields local to the processing facility.⁴ Some of these grains are milled to make flour, producing bran as a by-product.

Step 2: The flour is processed to produce vital wheat gluten, producing starchy water as a by-product.

Step 3: The starchy water left over when making vital wheat gluten is used to brew beer (substituting water), along with perennial grains (unmilled and malted) and any other ingredients depending on the beer style, generating brewer’s spent grain (BSG) as a byproduct.⁵

Step 4: The BSG leftover from brewing beer is used to make diverse products, such as miso, shōyu, knækbrød, meat analogues⁶ and even alt-choc.

Step 5: The vital wheat gluten is used to make different types of seitan, flavoured in different ways—either with ingredients produced offsite, or potentially some produced onsite, like bran amino, BSG shōyu, or fungal flavourings grown on BSG or other substrates. Some types of seitan could also be made with BSG as an additional base ingredient.

Step 6: The bran left over from milling flour is treated with enzymes to make bran amino, an umami-rich condiment, also producing a solid presscake as a by-product.

Step 7: The bran amino presscake is used as part of a substrate to grow diverse mushroom varieties on. Compost made from the spent fungal substrate is sent back to the farm as fertiliser where the perennial grain was originally grown, closing the loop.

Rather than producing any one of these foods in isolation (e.g. flour from perennial grains) and not making use of their by-products (e.g. bran), designing each process to use the by-product of another produces much more food overall—both in terms of diversity and volume.⁷ The theoretical system we have designed here produces beer, knækbrød, mushrooms, multiple umami-rich condiments, multiple protein-rich foods, and alt-choc. It's even possible to make a complete meal from all the foods produced in this system, like a seitan burger with mushrooms glazed with BSG shōyu in a perennial grain bun, served with a cold beer, and some chocolate for dessert.

This isn’t simply a yield argument. Industrial symbiosis for upcycling connects existing processes and their by-products that would be produced anyway into interconnected value loops that are more than the sum of their parts. It does not displace land-based production, but rather complements it by simultaneously reducing waste and making more (and more diverse) food from the same area of land without increasing pressure on biophysical systems. We think this is important to note, given the way that certain blackboxed statistics, like the claim that ‘we must double food production by 2050’, are often uncritically used to justify ideologies like ecomodernism that aim to maximise yields and decouple food production from land altogether.

iv. Endless possibilities

The example above illustrates just one possible design of industrial symbiosis for upcycling. Countless others could work just as well. The same by-products we use here could also be used to make different food products. To give but one example, depending on the other ingredients used, the spent mushroom mycelium could be used to make a shōyu instead of compost. Since the pressed shōyu solids contain salt, that by-product might be less well-suited to compost—but might instead find form in another food product, for example, if dried and milled. Such are the kinds of trade-offs necessary to weigh in designing such industrial-symbiotic systems.

The by-products used in this system (like BSG or cereal bean) could also be combined with different by-products (such as those from plant-based milk production) in alternative system designs built around similar principles. Likewise, entirely different combinations of by-products could be used—it isn’t necessary to use e.g. BSG or cereal bean at all. Which combination works best would depend on the context, including the types of foods and by-products produced locally, what food products might be culturally appropriate, and the desired scale of the facility. What if the system were designed to utilise diverse fruit and vegetable, coffee, tea or bread by-products? How this would work best would depend on the scale of the design. For a smaller system, it might make sense to utilise the by-products of an on-site bakery, restaurant or market garden. For a larger system, perhaps located on the periphery of a city, it might make more sense for the system to act more as a regional hub, sourcing these same by-products from a wider pool of restaurants, bakeries, juice bars or farms. This flexibility and scalability we see as one of the idea’s strengths.

Upcycling models that focus on a single by-product shouldn’t be disregarded outright. They can still deliver meaningful benefits and are certainly better than not upcycling at all. For instance, if a mill had the infrastructure to convert its bran into bran amino, but went no further, that would still be valuable in that specific context. Nevertheless, in many contexts, industrial symbiosis for upcycling may be best suited to overcome many of the barriers we described at the start of this article, whilst simultaneously reducing waste and producing more food from fewer inputs. While such systems may be more feasible in new or purpose-built facilities, there may be creative ways to retrofit existing operations with the same principles.

These possibilities prompt a deeper question: what values and visions of the future underpin the systems we choose to build? Josh and colleague Jamie Lorimer have written elsewhere about how, while fermentation is sometimes fetishised as inherently progressivist, it can’t actually possess an inherent politics as it is practised in so many different ways for so many different reasons. Rather, the goals of a particular practice, the values underpinning it, and the wider context it exists within all shape its politics, or ‘political zymology’.⁸ The same is also true for upcycling (which sometimes involves fermentation, at other times not), both in general and when designed around industrial symbiosis principles. A system utilising by-products of industrially-produced commodities at a massive scale could be designed around industrial symbiosis principles. Equally, a facility run as a workers’ cooperative, upcycling the by-products of agroecological, locally produced ingredients using microbial strains from a bioregional ‘microbial bank’ or open-source enzymes, could also be designed around such principles. Yet these two examples are guided by very different values, goals, and visions for society and political economy. Therefore, industrial symbiosis principles, although impactful, are alone insufficient to guide upcycling towards our preferred future, unless their goals and values are aligned accordingly.

These differences in values and visions don’t have to be limiting. Industrial symbiosis for upcycling could serve different functions over different time horizons, acting both as a pragmatic strategy for reducing waste now in the current system and as a visionary tool for shaping these systems in new directions. In the near term, it can create value out of existing industrial by-products, even within a wider food system that remains largely unsustainable. As the food system evolves, the principles of industrial symbiosis could help reconfigure what is produced, how it is produced, and who benefits. In this way, industrial symbiosis for upcycling could be a bridge between today’s realities and the more ecological, equitable and flavourful food system we hope to help build.

Contributions & acknowledgements

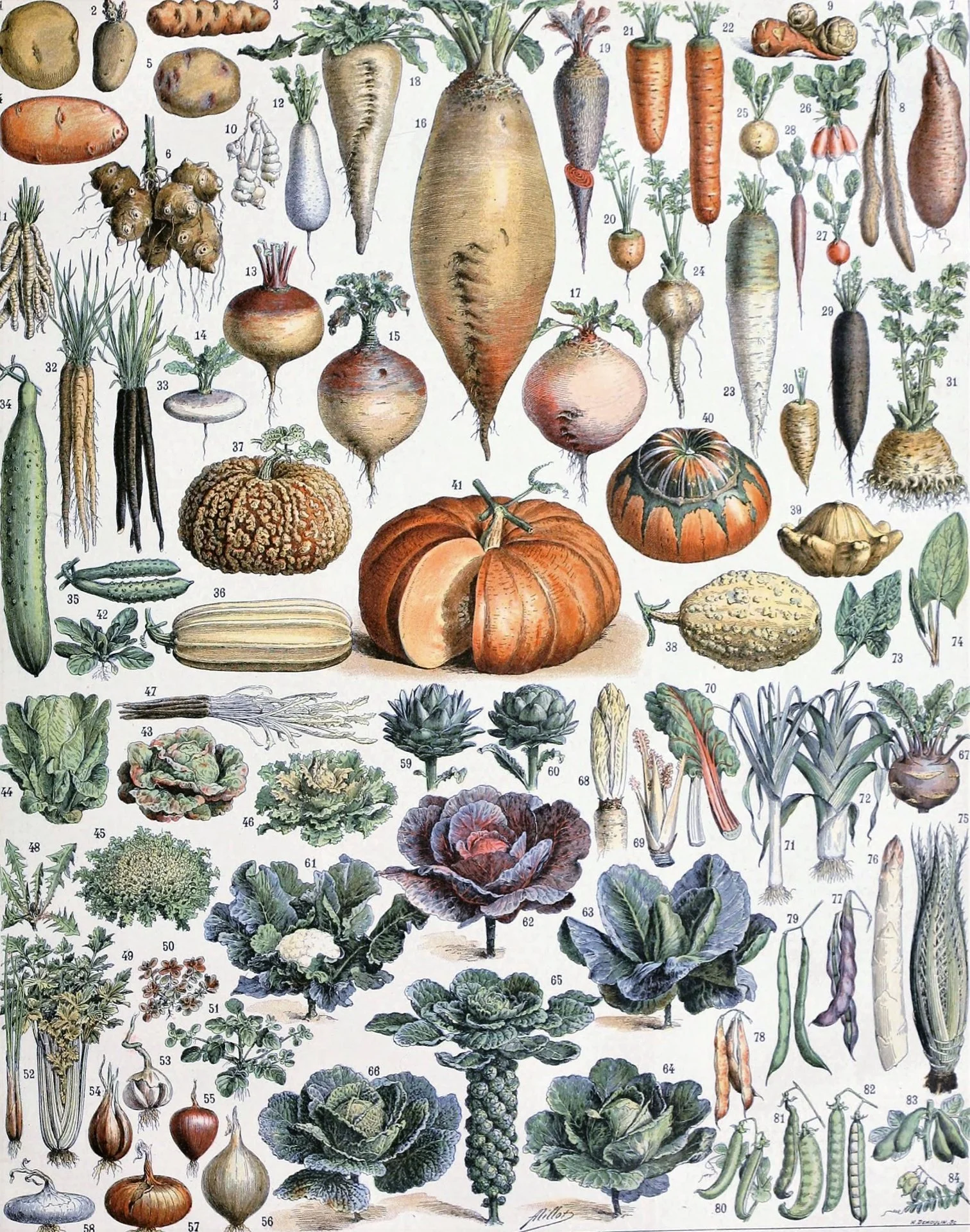

This essay arose from an idea Kim shared at our monthly group seminar. Eliot worked with Kim and Josh to turn it into a poster presentation for our centre-wide Annual Summit in 2024, before developing it further into this article. Eliot developed the images, based on the originals by Kim.

Endnotes

[1] Kost Studio (2025), ‘Making sidestreams mainstream’.

[2] Olcay Genc (2014), ‘Harmony in Industry and Nature: Exploring the Intersection of Industrial Symbiosis and Food Webs’, Circular Economy and Sustainability.

[3] We’re using this as a shorthand for a space where both food ingredients like vital wheat gluten and finished foods like miso can be processed or made.

[4] Perennialised grains (most famously Kernza), legumes and other crops are a promising form of amodern innovation that could support more agroecological futures. See Elizabeth Chapman et al (2022), ‘Perennials as Future Grain Crops: Opportunities and Challenges’, Frontiers in Plant Science; and elsewhere for more. Currently their yields aren’t high enough to be commercially viable (approx. 1 tonne per hectare; see Calvin Dick, Douglas Cattani and Martin Entz (2018), ‘Kernza intermediate wheatgrass (Thinopyrum intermedium) grain production as influenced by legume intercropping and residue management’, NRC Research Press) but in this future we imagine that this problem has been sufficiently solved. They appear to be particularly well-suited to this specific design, in which a specific facility is served by local agriculture rather than commodity grains from further afield; though the latter could also work.

[5] Depending on the style of beer being brewed, other grains may used in place of perennial grains. These grains could be sourced from elsewhere, either pre-malted or malted on site prior to brewing. Other ingredients, including hops, may also be added. Different beers styles would affect the characteristics of the final BSG being produced, which may in turn impact how it can be upcycled.

[6] This is something we’re currently developing in our food lab.

[7] We initially sought to include some rough quantification for each step, but were unable to fully calculate reliable yields representative of industrial-scale production for each product due to differences in efficiency between our R&D-stage food lab prototypes and optimised industrial processes, as well as the complexity introduced by multiple products being made in Step 5. Additionally, each food product requires supplementary ingredients beyond the by-products used within this system—for example, producing bran amino also requires the addition of water and enzymes. A direction for further research.