The Kojigotchi

The arts have long served not only to depict reality but to reform it—guiding society through states of rupture and repair by imagining alternative views on the world as it is—and, crucially, as it could be. Across our group’s transdisciplinary work—spanning culinary, scientific, and social dimensions—our approach is to engage with the arts as a critical instrument not only for reflection and intervention but as a methodology for probing the cultural, ecological, and political dimensions of our research.

It is within this ethos that Kojigotchi emerged.

The seed of the idea that would ultimately become Kojigotchi was first planted in the fall of 2024, when Taylor brought together Josh, Adrien Rigobello (Royal Danish Academy), and Maxim Velli (Learning Planet Institute) over video call—each dialling in from different cities: Paris, Copenhagen, and Barcelona. Born from Maxim’s initial vision of a biological Tamagotchi, early conversations circled the idea of a portable incubator for cultivating fungi—a handheld chamber of sorts for growing mycelium-based materials.

Though the concept was still embryonic then, the desire was clear—to mobilise the inherent livingness of our potential microbial collaborators to prompt play, spark curiosity, and encourage stewardship. What was concrete, however, was the plan hatched during that first meeting—to begin working in earnest, and in person, at DTU the following spring.

And so when March arrived, Maxim did too, and the work began in full stride. By April, two additional and essential team members had joined: Rasmus Tofthøj, who took charge of physical prototyping, and Tania Safa, who started shaping the project’s visual narrative. Not long after, we were joined by our final collaborator—one from a different kingdom of life entirely: Aspergillus oryzae.

The pivot from mycelium materials to an edible ferment felt organic. Not only did it connect naturally to our group’s research, but it also shifted the tone of the device itself. With A. oryzae, the living aesthetic of Kojigotchi became more intimate—an object not just for cultivation, but for consumption in the most interfacing and immediate ways, illustrating the porous exchanges between human and microbial life.

Now that the project was both figuratively and literally coming to life, we had to contend with our June deadline—a date circled not just on our calendars but set by the 2025 Biodesign Challenge summit. The BDC Summit, an annual gathering in New York City, is part competition, part conversation: a stage where students and practitioners from around the world come together to collectively imagine, prototype, and critique the future of biotechnology. Projects presented at the summit span speculative artefacts, lab-ready tools, and poetic interventions—each asking how emerging biotechnologies can shape, or be shaped by, political conditions, cultural values, and ecological considerations. For us, BDC offered both a proving ground and a provocation—a reason to compress months of development into weeks, and to shape Kojigotchi not just as a technical product but as an object that could foreground questions of care, reciprocity, and the permeable boundaries between human and microbial life.

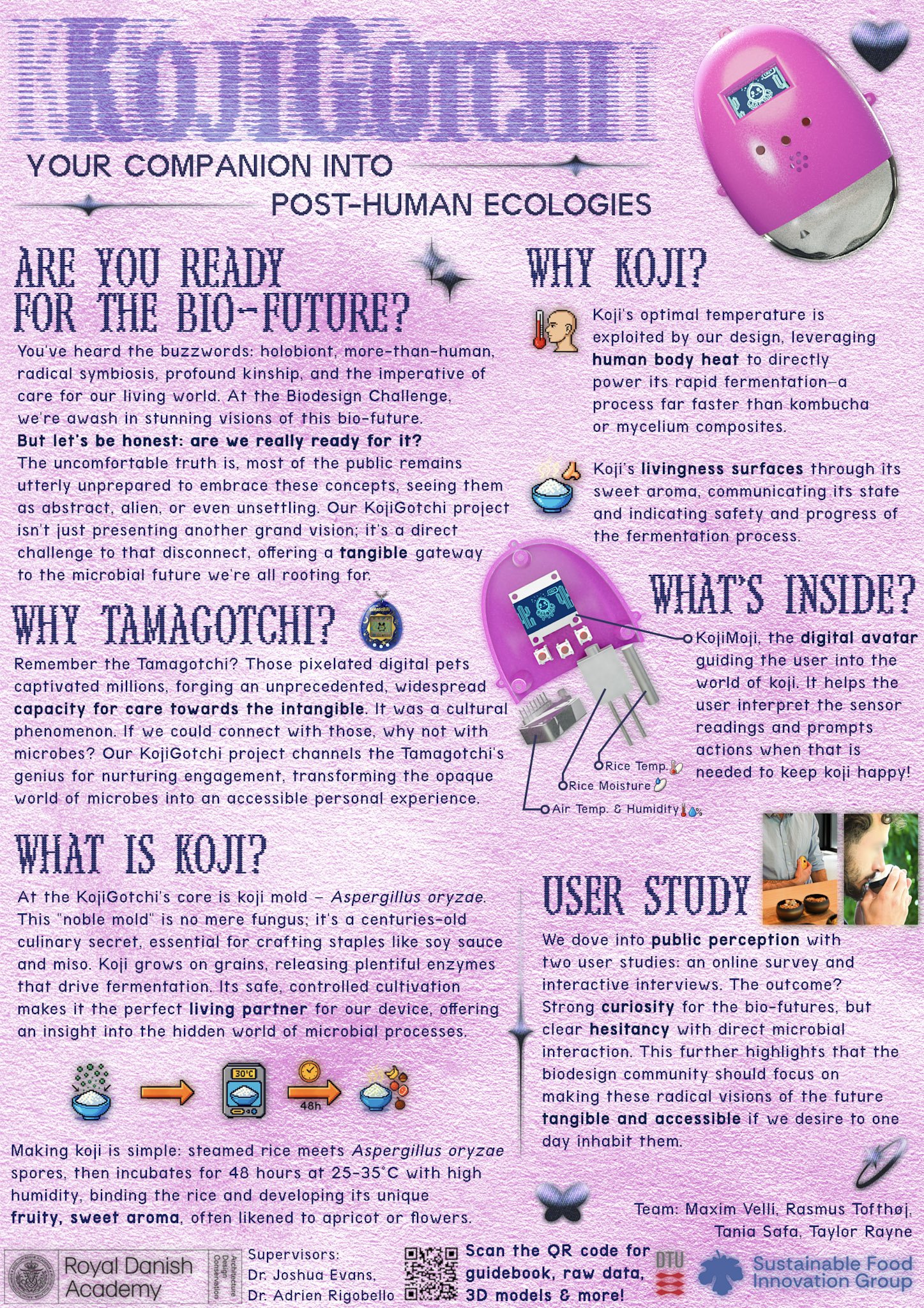

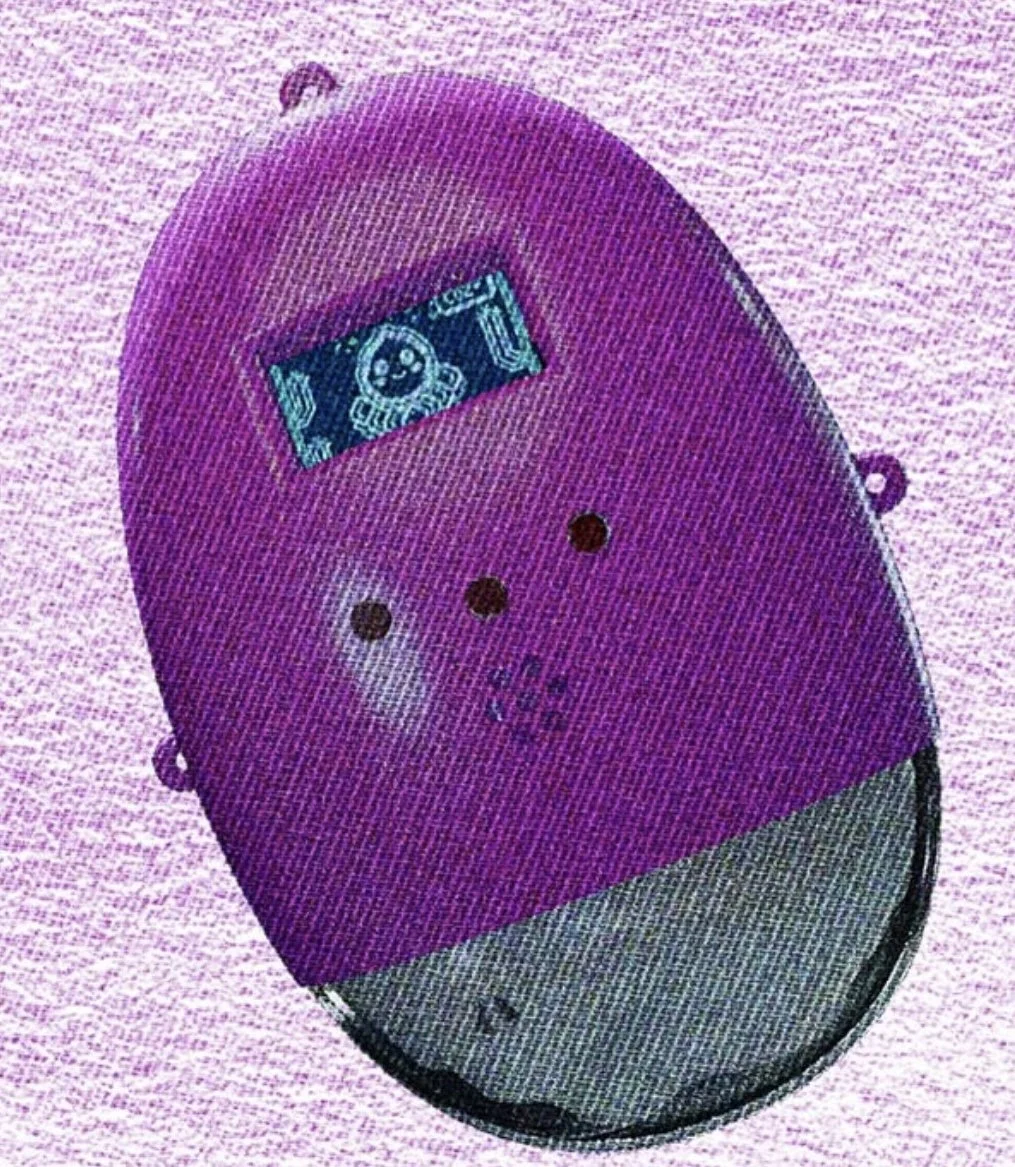

This framing shaped not only our deliverables but our approach: crafting a bio-artifact that would stimulate dialogue as much as demonstrate technical possibility. Drawing inspiration from the 1990s handheld virtual pet, the Tamagotchi, our project borrows the former’s retro-futurist aesthetic and interactivity to reframe microbial life as essential partners in our homes, bodies, and technologies.

In our case, the ‘pet’ is Aspergillus oryzae, a filamentous fungus foundational to fermentation practices across East Asia. When cultivated on rice or other grains, this fungus creates kōji—a living substrate that transforms raw ingredients into sake, miso, and soy sauce. Beyond its culinary significance, kōji represents a history of symbiotic co-evolution, an organism domesticated through mutual benefit and reverence. By situating kōji within a device worn on the body, Kojigotchi invites users into a multispecies collaboration—where the users’ own body heat incubates growth, cultivating not only the kōji but also an intimate moment of care that embodies mutual interdependence and co-production.

Thus, the development of Kojigotchi demanded an ongoing negotiation between microbial needs, user ergonomics, and aesthetic form. Designed as a passive incubator, the device houses the substrate and growing fungus within a transparent chamber pressed gently against the skin, allowing body heat to support growth. Balancing exposure with viability was a delicate challenge: allowing some airflow gave the fungus ample oxygen and let the user smell the growing fungus, but too much risked drying the spores, while too little could lead to user neglect. Throughout the product design process, we cycled through multiple rounds of user testing—between the lab bench and everyday wear trials—to refine the device’s materials, fit, and interaction. In order to simultaneously serve user experience and support the kōji’s microclimate without compromising comfort, the team engaged with other members of our group across our culinary, scientific, and cultural expertises. Throughout this process, guidance in fermentation and microbial ecology informed technical decisions, while critical perspectives on the cultural and ethical dimensions of living with microbes enriched our thinking and shaped the design process.

The final Kojigotchi prototype emerged not only as a bio-incubator but as a thoughtful intervention—inviting reflection on how humans can imagine, coexist with, and nurture microbial life.

Maxim and Tania present the Kojigotchi at BDC 2025, at Moma PS1 in NYC

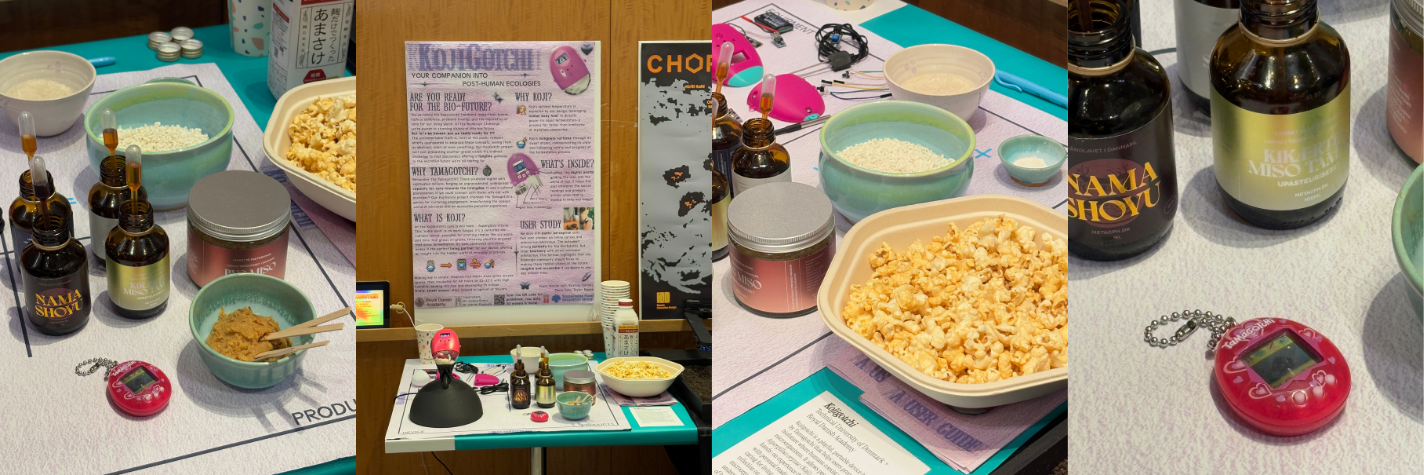

Our poster and prototype display for the Kojigotchi at BDC 2025, at Moma PS1 in NYC

Our poster in full

In New York, the device sparked a range of reactions from fascination to discomfort, igniting conversations among our fellow BDC summit attendees about intimacy, microbial presence, and biotechnological futures. Serving as a medium for multispecies dialogue, Kojigotchi demonstrated how design can open critical spaces for cultural and ecological inquiry. More broadly, the project embodies a commitment to transdisciplinary research, poetic speculation, and ecological attentiveness. It reflects the belief that shaping the future requires approaches that are both scientific and sensorial—rooted equally in lived experience and imaginative exploration.

While Maxim continues refining the project, Kojigotchi has already prompted a disposition that outlasts the device itself: a commitment to approaching biotechnology not as a solved domain but as a field shaped by uncertainty, negotiation, and imagination. Working across design, microbiology, and cultural inquiry demanded that we continuously reassess our assumptions—about what counts as care, what constitutes collaboration, and how microbial life can be meaningfully integrated into everyday experience.

Seen this way, the project becomes a reminder that biodesign is most generative when it remains unsettled, when it entertains possibilities rather than closes them down. Kojigotchi stands not only as a prototype but as a gesture toward more open, inquisitive futures, where living systems are engaged with attentiveness, reciprocity, and critical curiosity.

For more details, visit the project website.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Maxim and Taylor extend their deepest thanks to Josh and Adrien for their supervision, and to Josh for his guidance on microbial cultivation and conceptual framing and for hosting the project; to Kim for his expertise on Aspergillus oryzae; and to Eliot for his moral support throughout the project’s development. Gratitude also to collaborators at Skylab—especially Rasmus Tofthøj—for their material and intellectual contributions.

The project was funded through generous support from the Partnerships and Research Office at DTU Biosustain. Our thanks to Dr Dina Petranovic Nielsen, our Chief Scientific Officer and Chief Partnerships Officer, for providing this funding, and to Hanne Varmark, our Head of Finance, for her support in managing the budget.