Spontaneous kombucha

This scientific digest is based on a paper written by Kim, Caroline and Josh called ‘Possible historical origins of kombucha in spontaneous fermentation’, currently in pre-print. That study emerged from Kim’s R&D at former Restaurant Amass in Copenhagen. Read the full paper for more.

Table of Contents

i. Mother of all mysteries

Have you ever received a kombucha mother or SCOBY¹ from a friend or benevolent online stranger and wondered where it truly came from? Yes, it came from that person’s previous batch of kombucha, but where did their original mother come from? And the one before that?

It’s not a silly question. Kombucha mythology abounds, and its exact origins remain speculative, having never been conclusively determined. If the kombucha mother looming in your fermentation vessel isn’t from some unbroken lineage shared by all kombuchas traceable back hundreds or thousands of years to some ancient land (spoiler: it likely isn’t²), then where did it come from?

We offer a potential answer to this question by drawing on historical, microbiological, ecological and evolutionary perspectives, and years of culinary tinkering, to establish a proof-of-concept for how kombucha microbial communities could assemble and form the beverages and biofilms we know and love—both now and in the past—by bringing together selected environmental sources of microbes in a sweetened tea medium.

ii. Initial experiments

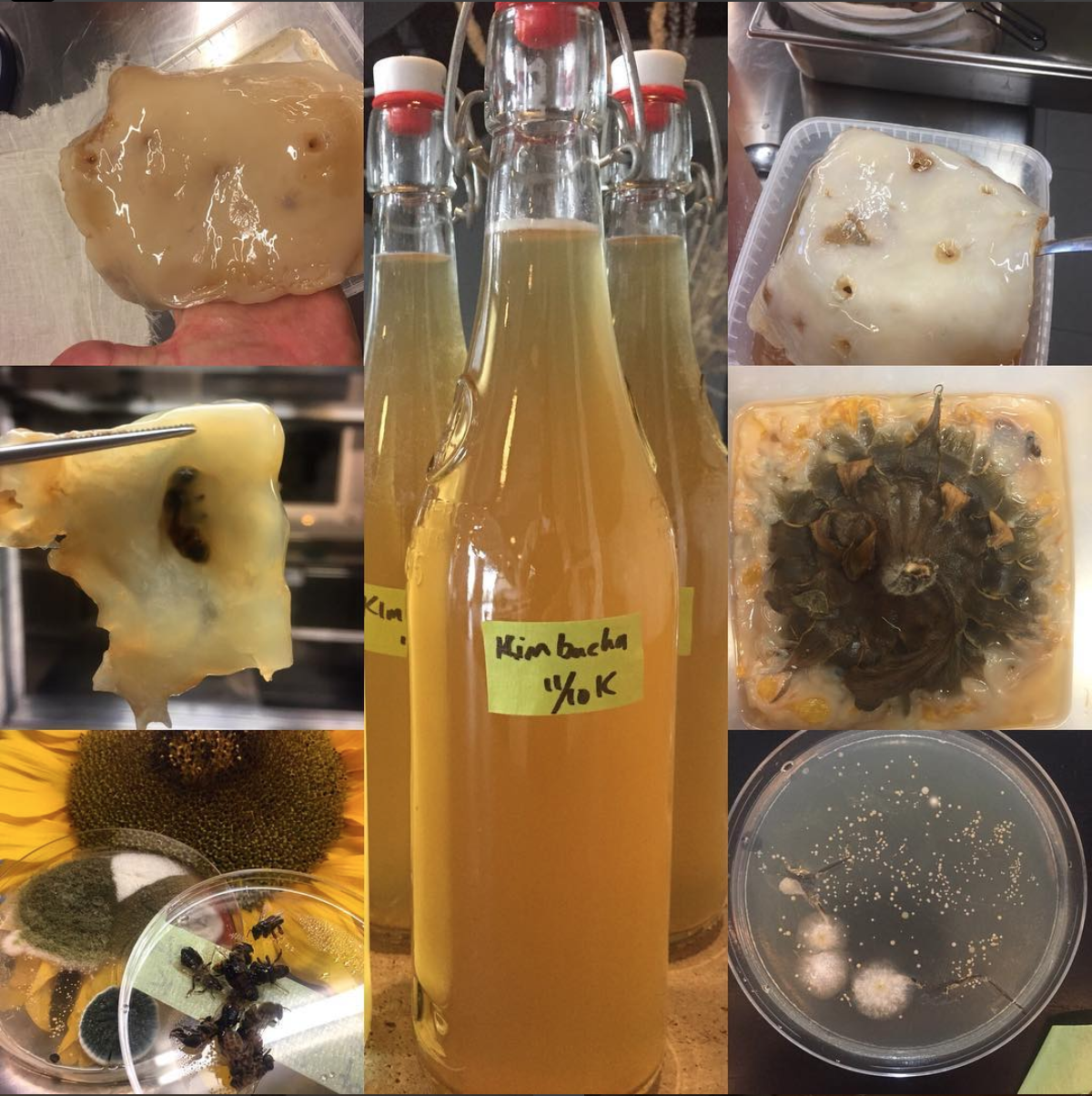

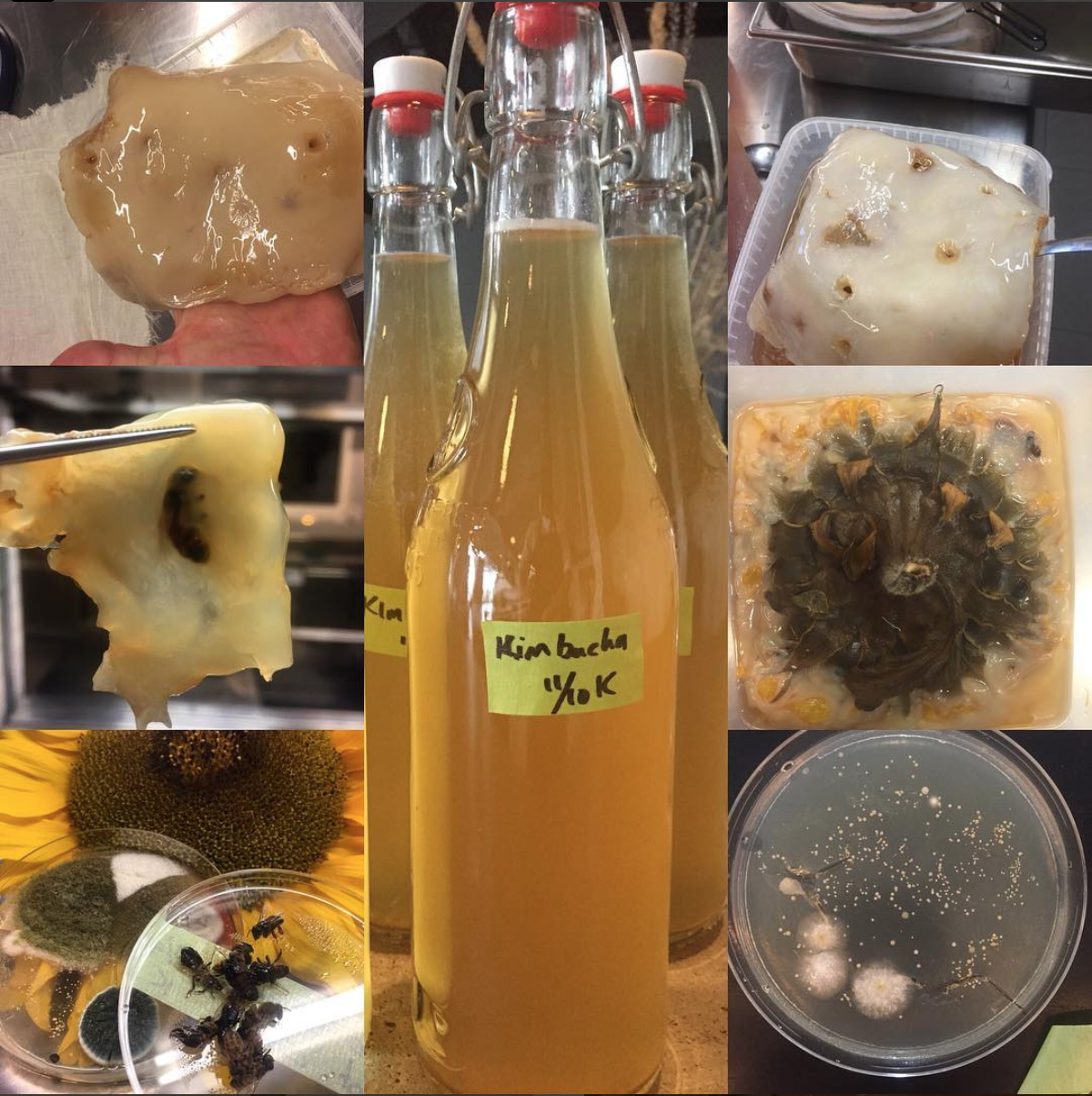

Kim first conceived the idea of creating a spontaneous kombucha in 2016 while working at former Restaurant Amass here in Copenhagen. He was motivated to do so, as, in his own words, he ‘dislikes the mysticism that so often seeps into fermentation. Though it may seem magical, it isn’t magic—just communities of microbes doing what microbes do.’ At Restaurant Amass, he conducted experiments with green tea sweetened with honey that he inoculated with microbially rich ingredients from the restaurant’s garden he knew were likely carriers of the key taxa in kombucha communities. He chose sources from insects, plants, and humans: honeybees which are known carriers of yeasts and bacteria³; sunflowers, as the bees likely collect microbes from the flowers they pollinate; and swabs from his own skin, since humans engaging in fermentation practices may contribute relevant microbial species, an idea known as son-mat or ‘hand taste’ in Korean. After some days, he noticed a small biofilm begin to grow at the edge of the sunflower. He transferred that to a fresh batch of sweetened tea, and eventually it grew to cover the surface, and the liquid acidified and bubbled and tasted like a kombucha—what internally became affectionately known as the ‘kimbucha’.

Kim repeated this experiment a few times. With his colleague Henry he also made another with a different combination of ingredients, this time accidentally—they added some beach rose petals to a rye bread kvass hoping to add their flavour, but a biofilm formed there too. This one they dubbed the ‘breadbucha’. These results showed that Kim’s findings were not only reproducible across systems and substrates, but that they also form spontaneously even when not intended.

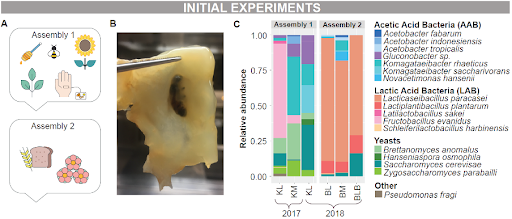

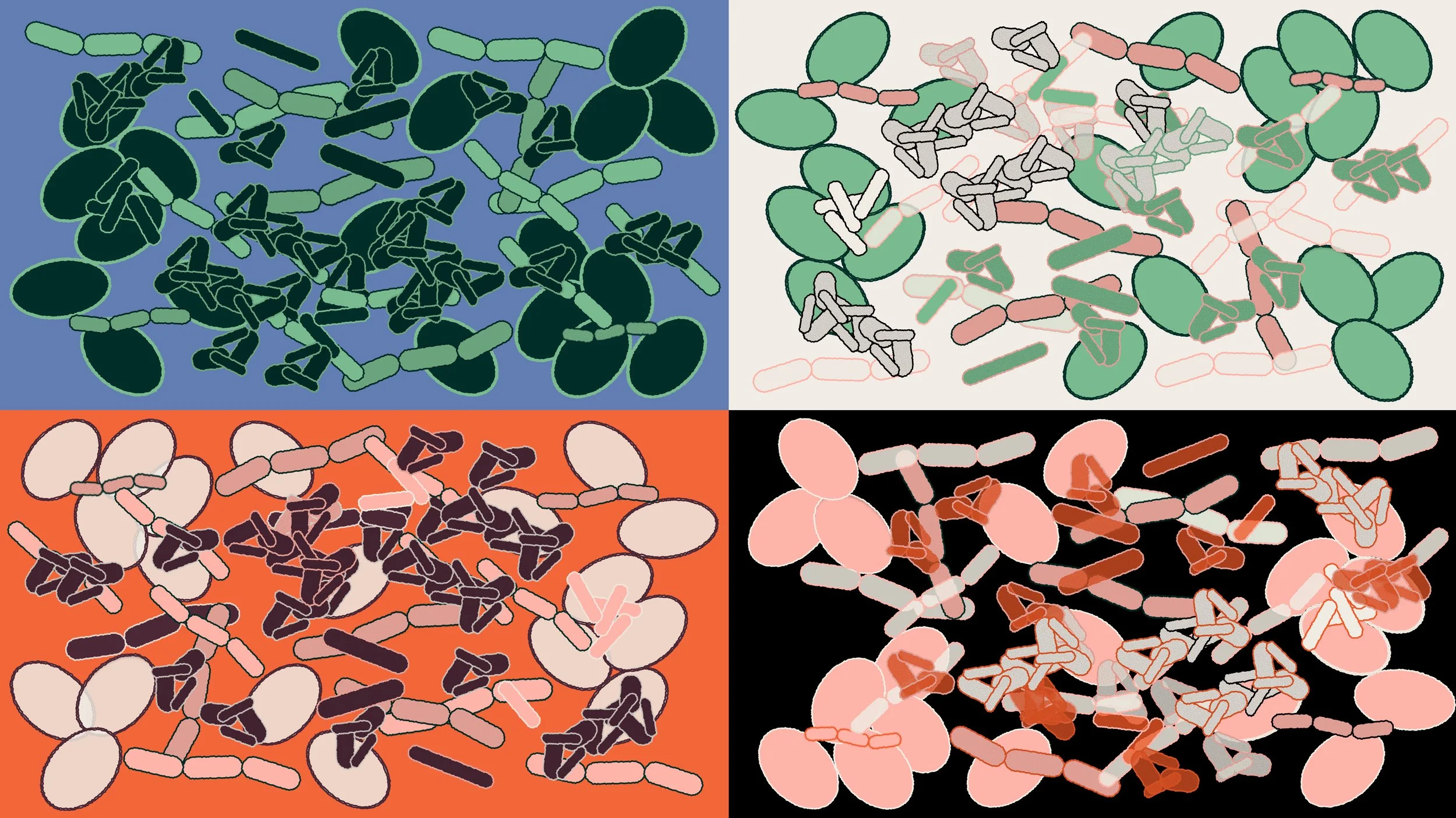

At the time Josh was doing his PhD, and got fascinated by Kim’s spontaneous kombucha experiments. He took some samples and together with collaborators at the University of Copenhagen used metagenomics to identify which microbes were present, and to see how similar to ‘real’ kombuchas these beverages were microbiologically. Both samples contained similar microbes at the family level: Acetobacteraceae (AAB), Lactobacillaceae (LAB), and Pichiaceae and Saccharomycetaceae (yeasts). The relative proportions between the two were different: the ‘kimbucha’ was mostly dominated by AAB and yeast (except for the liquid sample from 2017), whereas the ‘breadbucha’ was dominated by LAB (Fig.1).

Figure 1: Initial trials and microbial composition results.

Image made by Caroline for the original publication.

Kim and Josh were intrigued and wanted to go deeper.

iii. Microbial community coalescence

These promising observations led Josh and Kim, now joined by Caroline in our (then relatively newly formed) research group, to design a more extensive, systematic research project to try to answer the following questions:

How does the microbial community develop over time?

Do the inocula (the sources of microbes) contribute to the community and biofilm formation, and if so, how?

How microbiologically similar are our spontaneous beverages to existing kombuchas and other fermented beverages?

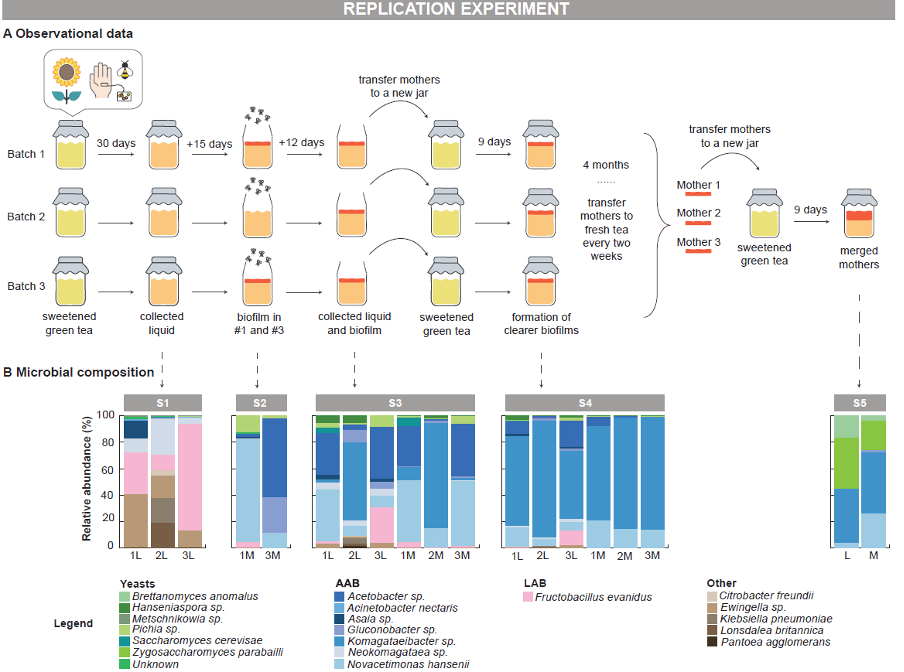

To answer these questions, we made three batches of ‘kimbucha’ in our food lab, again from scratch using the same ingredients as before, and sampled them multiple times over a six-month period to identify how the composition of their microbial communities changed over time (Fig.2).

Figure 2: Replication experiment design and microbial composition results.

Image made by Caroline for the original publication.

The microbial community of the ‘kimbucha’ evolved over six months of fermentation. Early samples were dominated by AAB and LAB, and had developed an acetic aroma, but no biofilms (mothers) had yet formed. After about 45 days the samples were rich in AAB and Pichia yeasts and mothers had formed, coincident with fruit flies being found around the samples. As fermentation progressed the samples became increasingly AAB-dominant, with other species such as Neokomagataea hansenii and Komagataeibacter saccharivorans also present at different stages. After almost six months, we merged the batches and sampled again nine days later. The final ‘kimbucha’ remained AAB-dominated but also gained additional yeasts like Brettanomyces anomalus and Zygosaccharomyces parabailii, similar to the community composition seen in Kim’s original spontaneous kombucha experiments.

The inocula contributed to the early stages of the spontaneous fermentation by providing the microbes that helped establish conditions for biofilm formation, though most inocula-associated microbes were not detected in later stages. In early stages of fermentation, Pantoea sp. from the sunflowers and Ewingella sp., Fructobacillus spp. and yeasts from the honeybees were detected. Though none were detected in later stage samples, these microbes likely facilitated the development of the climax microbial community in the ‘kimbucha’. Pangenomic analysis of Fructobacillus evanidus shows the beverage strains are closely related to bee-associated strains, confirming transfer from the bees.

We then compared our samples with metagenomic datasets from other fermented beverages like kombucha, wine, water kefir, vinegar, pulque and lambic beer using a statistical method called principle component analysis (PCA), which clusters samples in two dimensions based on their relative similarity. Both the ‘kimbucha’ and ‘breadbucha’ were microbiologically very similar to standard kombuchas, particularly in their later fermentation stages. Early samples of the ‘kimbucha’ were less microbially similar to standard kombucha due to higher LAB presence, but gradually shifted toward a classic kombucha-like microbial community profile dominated by AAB. The ‘breadbucha’ slightly more closely resembles water kefir but remains mainly aligned with kombucha. We also detected potentially novel microbial species, which highlights the broad and still largely unmapped microbial diversity that emerges during early spontaneous fermentation.

The ‘kimbucha’ mother

iv. Implications for kombucha origins

This proof-of-concept can help explain the possible origins of kombucha in spontaneous fermentation, and how its microbial communities develop and stabilise over time and form mothers. Kombucha might have emerged in the past through a similar interaction of environmental microbial communities in nutrient-rich liquid conditions. During the many centuries that humans have been drinking tea sweetened with honey, it's likely that skin microbes of the people brewing or drinking the tea sometimes found their way into the tea when it was cool enough for them to grow. Microbes from bees or other insects, or airborne pollen, or other microbially-rich sources from the environment, could easily have found their way in as well, perhaps by falling into tea unintentionally left exposed, or added intentionally, for e.g. medicinal reasons.

That Kim was able to produce kombucha-like beverages with two totally different sets of microbially rich inoculants, one entirely unintentionally, only strengthens this argument. Many other combinations could also conceivably exist. Throughout the long history of humans drinking tea, suitable combinations of microbially rich ingredients, drawn from a global pool of possible inocula, could have found their way into a vessel of sweetened tea and produced kombucha through this process. This diversity of potential microbial sources, paired with the relative ease with which such communities can form, suggests it is likely that kombucha has multiple different origins, rather than just one from which all have descended.

Fascinatingly, various mythologies and folk explanations for kombucha origins could, at least in part, be explained by this process, like the legend of a Russian emperor being healed by a monk who advised him to put an ant in his tea to form a ‘jellyfish’-like structure with healing properties.⁴

Many other traditional fermented foods also likely emerged in similarly serendipitous circumstances.⁵ Cheese may have first been discovered when milk was stored in vessels made from ruminant animal stomachs, which, since they contain the enzyme rennet, caused the milk to coagulate, making the first cheeses, which were then adopted and refined over time. The mechanism identified in our study suggests something comparable could be true for kombucha’s origins.

More generally, this research project has, for us, been a nice reminder of the importance of always questioning received wisdom—both in science and in fermentation practice. Both of these communities and bodies of work still share the orthodoxy that a kombucha can only be made from an existing one, which alone is not able to account for how it might originally have emerged. While established knowledge of course helps guide is in practice and research, it can also blind us to and even actively foreclose possibilities for thinking otherwise. Keeping that curiosity and imagination alive—in this case particularly through the cheffy approach to tinkering and testing boundaries of knowledge—is a valuable sensibility, in fermentation research and practice alike.

Read the full paper at: ‘Possible historical origins of kombucha in spontaneous fermentation’.

Contributions & acknowledgements

This scientific digest is based on original research by Kim, Caroline, Josh and colleagues. For a full list of contributions and acknowledgements for the research project, see the original paper. Eliot wrote this scientific digest based on the manuscript, with editorial input from Josh. Kim photographed the images used as the composite header image. Eliot photographed the mother in our food lab.

Endnotes

[1] Though the term SCOBY (Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeast) is often used to refer to the jelly-like pellicle or biofilm that forms at the top of a fermenting kombucha, microbiologically speaking it refers to the microbial communities themselves, of which the biofilm is a by-product.

[2] Even though kombucha’s origins are unknown, there’s no credible evidence to suggest that all kombucha SCOBYs share a single origin, as romantic as that would be.

[3] Nsikan Akpan, Matt Ehrichs & PBS NewsHour (2017) ‘The Beers and the Bees: Pollinators Provide a Different Kind of Brewer’s Yeast’, Scientific American.

[4] Hannah Crum and Alex LaGory (2016), ‘The Big Book of Kombucha: Brewing, Flavoring, and Enjoying the Health Benefits of Fermented Tea’, Storey Publishing: North Adams, Massachusetts, USA.

[5] Dillon Arrigan, Caroline Kothe, Angela Oliverio, Josh Evans and Benjamin Wolfe (2024), ‘Novel fermentations integrate traditional practice and rational design of fermented-food microbiomes’, Current Biology