What are novel fermentations?

This article draws on the scientific paper ‘Novel fermentations integrate traditional practice and rational design of fermented-food microbiomes’ [pdf], authored by some of our team and collaborators and published in Current Biology.

Table of Contents

i. What are novel fermentations, and why do they matter?

Fermentation has experienced something of a renaissance in the Western world in the past decade or two, though it has long thrived elsewhere. Chefs, home fermenters, and others have been tinkering with traditional methods in new contexts, combining different ingredients, microbes, and techniques to create a wide range of novel fermentations with unique flavours, textures, and culinary applications.

Beyond the mere appeal of novelty, new ferments may play a key part in shaping more sustainable food systems: they enable the upcycling of underutilised food by-products, transforming what is often considered inedible into further nourishment;¹ offer a rich palette of techniques to ‘umamify’ plant-based ingredients; and reveal ways to unlock new flavours for more bioregional food production. For these reasons, novel fermentations are central to our group’s research programme, through which we make and study them using culinary, scientific, and cultural lenses.

But what exactly counts as a novel fermentation? How might we classify different types of novel fermentations? And why do we even care to classify what is novel and what is not?

Currently, there is no consensus on where and how to draw appropriate boundaries between ‘novel’ and ‘traditional’ fermentations. And perhaps such a universal agenda is unnecessary, if it were even possible, as any answer to this question will likely depend on the context and objective. Acknowledging this complexity, we recently contributed to two papers that sought to address this question in different ways.

The first is ‘Old Foods, New Forms’, in which Josh, Taeko, Nabila, and colleagues at the European Miso Institute take a culinary and cultural approach to categorising novel fermentations. They develop a conceptual framework with seven categories, based on how the ingredients, production process, and sensory profile of a given novel fermentation differ from a comparable traditional product. Some of the categories they propose include ‘analogue’ products with standard production processes and sensory profiles, but non-standard ingredients, like novel misos and plant cheeses made from coagulated plant milks; and ‘experimental’ products, with standard production techniques but non-standard ingredients and sensory profiles, like dairy misos and yeast ‘garums’.

Another way of classifying novel fermentations draws upon principles from microbial ecology and evolutionary biology. Josh, Caroline, and colleagues at Ben Wolfe’s lab at Tufts took this approach in a recent paper called ‘Novel fermentations integrate traditional practice and rational design of fermented-food microbiomes’. Here they define novel fermentations as ‘the confluence of traditional food practices and rational microbiome design,’² with rational design referring to ‘the systematic and deliberate approach to experimenting with substrates, microbes, and fermentation conditions to produce novel outcomes.’

Though they note that they ‘are also not sure that such a line [between novel fermentation categories] could ever be conclusively drawn’, and ‘propose that multiple ways of drawing these boundaries could be equally useful and suited to different purposes’, the authors propose four categories in which novel fermentations can be classed based on microbial community assembly principles.

In this article, we will describe how this approach sheds light on how community interactions shape novel ferments, discuss why this way of categorising could be useful, and explore how it could guide further tinkering and innovation.

ii. The science behind novel fermentations

Through trial, error, and taste, humans have long been shaping the ecology and evolution of microbial communities in fermented foods. Many of the earliest ferments may have first emerged serendipitously, as our ancestors sought ways to nourish themselves and their communities amid environmental constraints and opportunities. While many instances of ‘accidental rot’ likely led to spoilage, other experiments that pleased our ancestors’ palates would have been gradually iterated upon, eventually resulting in many of the ferments we celebrate today. Indebted to generations of patience and persistence, our understanding of fermentation continues to grow, and with it, our ability to more intentionally guide microbial labour.

Achieving this more intentional relationship with microbial communities involves facilitating a conversation between controls of food production and the microbial responses that shape community dynamics through ecological interaction and evolutionary change.

To understand and guide the dynamics of microbial community assembly for the design of fermented food products, we can turn to three key questions, which we explore through the example of miso—apparently our favourite ferment.

Tinkering, iterating, and tasting new things have led to the creative diversity of traditional ferments and this ongoing trajectory of experimentation. Now complemented by scientific insight, these processes of dispersal, selection and diversification continue, guiding the trajectory toward future fermentation for desired flavour profiles and aesthetic and functional outcomes.

iii. Classifying novel fermentations based on microbial processes

Understanding how microbial communities form and evolve can help us categorise novel fermentations in more systematic ways, across specific cultural and geographic contexts.

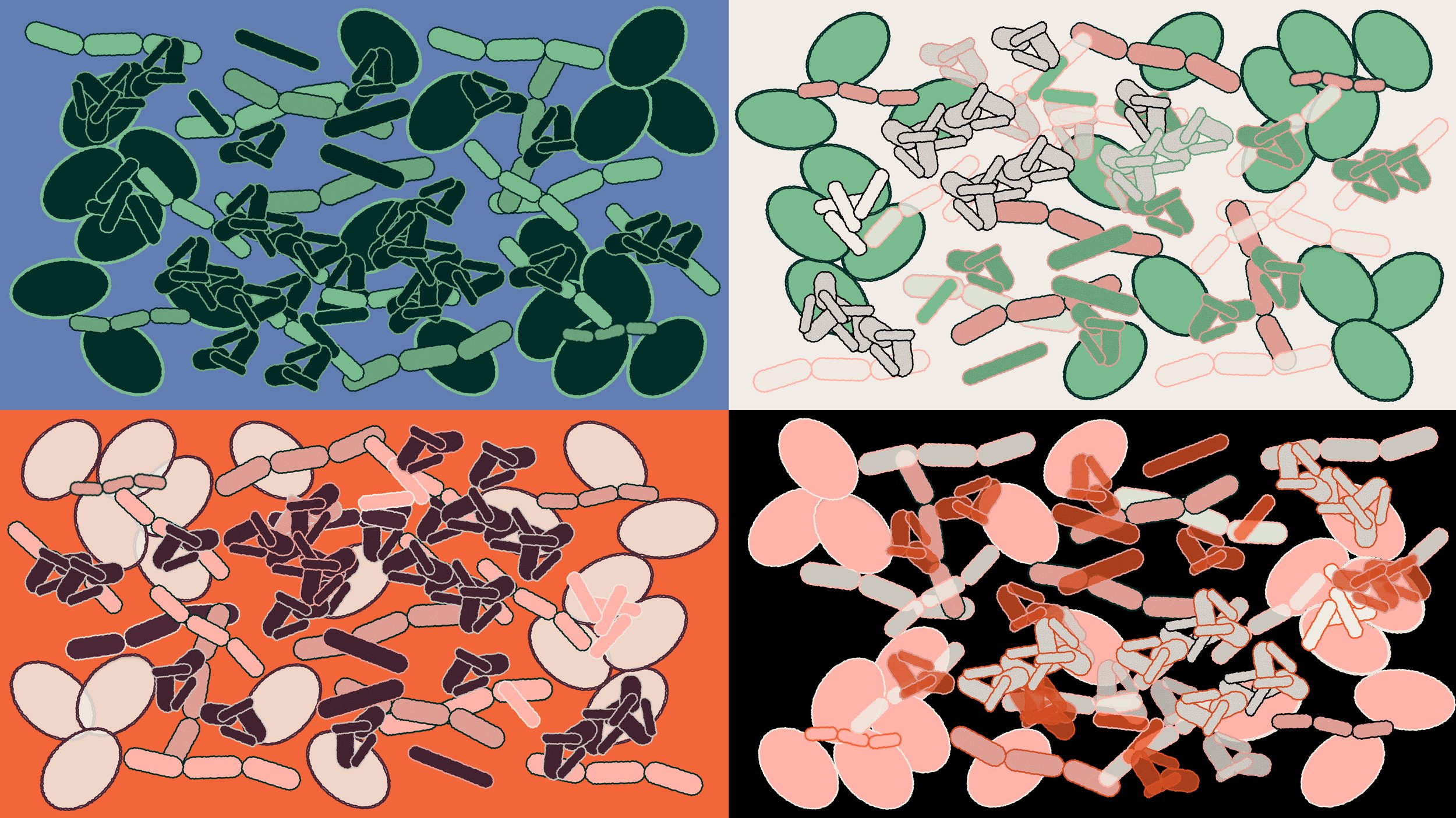

Figure 1 outlines a framework for categorising novel fermentations based on key microbiological principles. These categories are not mutually exclusive; rather, they allow the same product to be framed in multiple ways, each highlighting different forms of novelty and lines of scientific inquiry.

Figure 1: Novel fermentation categories (adapted from Arrigan et al 2024).

a. Switching substrates

Novel fermentations in this category are probably the most familiar, including many that we in the group make and study. The goal here is to transfer the functional diversity of a traditional ferment’s microbiome to a novel substrate (new ingredients), either by intentionally adding microbes (inoculation), introducing them from some of the previously finished ferment (backslopping), or letting them naturally emerge (spontaneous fermentation). Each can be done in different ways. Growing kōji on untraditional grains and legumes is a good example of the first. Making kombucha with fruit or vegetable juices would be an instance of the second. And novel misos nicely illustrate the third.

b. Engrafting target species

A second way of creating novel ferments seeks to add the functions of a given microbial species to a ferment where it is not normally found. One example is using kōji (A. oryzae) on a surface-ripened cheese instead of a more traditional mould like Penicillium sp.³ The result is still made of animal milk and is immediately recognisable as cheese, but also has a novel flavour due to the engrafted kōji. This same method could be used to generate all sorts of novel flavours, textures and other properties in fermented foods.

c. Assembling whole-community chimeras

Rather than switching substrates or introducing individual species, this third category involves mixing whole microbial communities from two or more existing ferments to yield a novel microbial community with distinct interactions and functions. When different microbial communities come into contact and form a new, merged ecosystem, it is known in microbial ecology as community coalescence. Here the outcome is a novel fermented product that might feature traits from both originating communities, and/or something entirely new, depending on how the microbes interact.

This category has undeniably rich potential but is still relatively underexplored (at least within the scientific community), to such an extent that, at the time of publication, the authors couldn’t provide a scientifically described example. Since then, Caroline, Kim, and Josh have submitted an article for one, based on Kim’s long-standing experiments with generating spontaneous kombucha ecologies (currently in pre-print).

d. Generating novel phenotypes

Finally, novel fermented foods can also be made by generating new microbial traits (phenotypes) by encouraging the microbes themselves to mutate or evolve. Unlike the first three categories, this approach focuses on changing the genetic makeup of the microbes involved in the fermentation to create novel genotypes and phenotypes—microbes with new capabilities, flavours, or textures—that could open up many new possibilities for novel fermentations.

There are different ways to do this. Microbial diversification through experimental evolution can be guided in the lab to evolve new traits on traditional substrates under different conditions, as Josh and his culinary collaborators did with kōji. Alternatively, microbes can be directed to adapt to new substrates, such as evolving dairy microbes to be better suited to plant substrates, as Caroline, Mathieu and Kacper are working on. Random mutagenesis can also be used to generate genetic mutations by exposing microbes to UV light or chemicals. For example, creating an ‘albino’ strain of the blue cheese mould Penicillium roqueforti gives rise to the growth of white colonies instead of blue, resulting in pure white ‘blue’ cheese.⁴

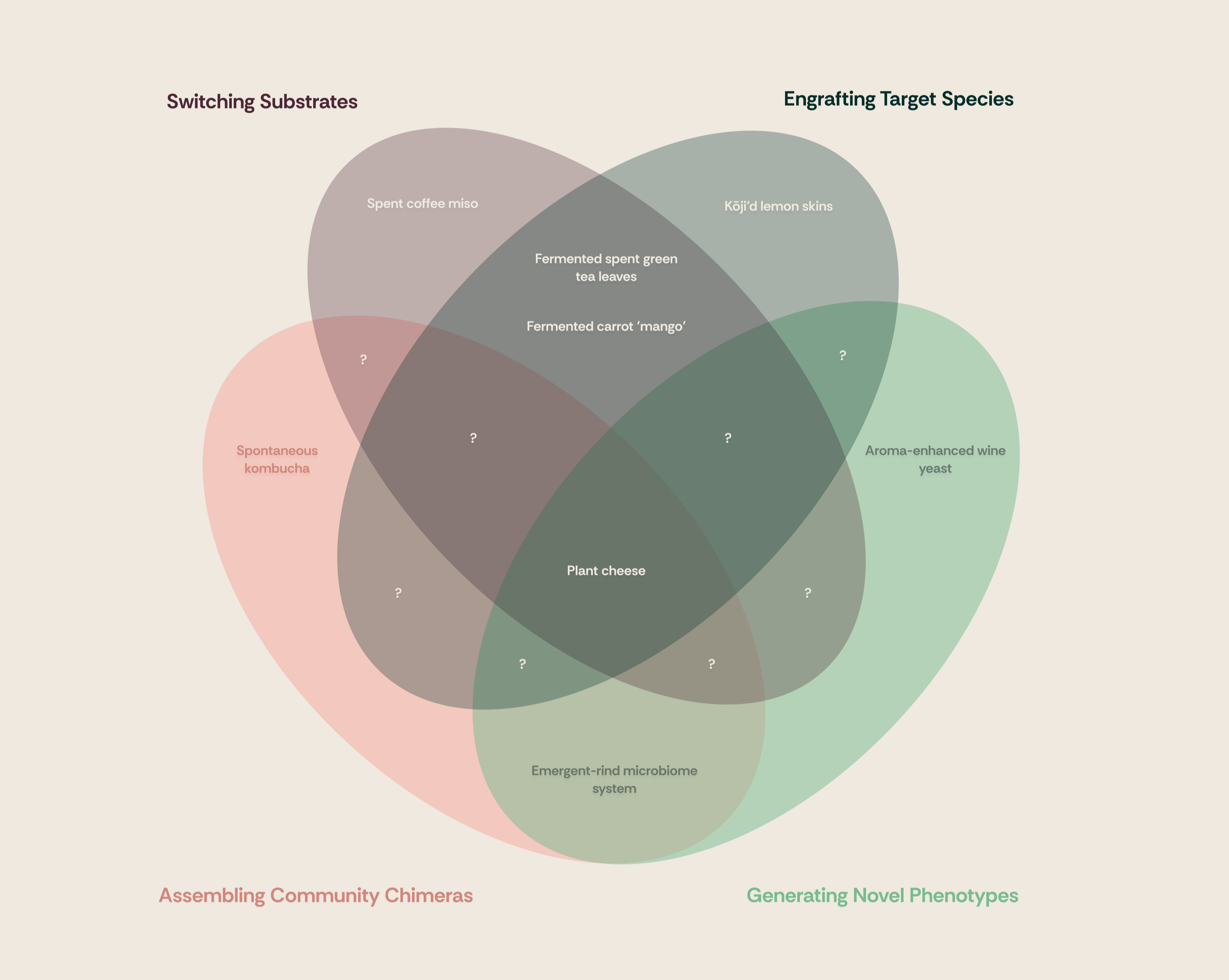

Figure 2: Novel fermentation categories aren’t mutually exclusive; combining multiple categories offers additional potential. For more on the listed examples, see: Spent coffee miso, Kōji’d lemon skins, Spontaneous kombucha, Aroma-enhanced wine yeast, Fermented spent green tea leaves, Fermented carrot ‘mango’, Plant cheese, and Emergent -rind microbiome system. We invite the reader to think of where additional examples might go (including the as-yet unpopulated fields with question marks).

iv. Fresh possibilities

As our scientific understanding of fermentation deepens, we can revisit traditional techniques with new tools and renewed curiosity. Yet the microbiological framework of novel fermentations we outline here can be used not only to study fermentations in new ways; it can also be used to guide and open up new directions for innovation.

For example, one important theme in culinary R&D, ours and others’, is the umamification of plant foods. Lots of R&D in this space has focused primarily on switching substrates. This approach has resulted in all sorts of deliciously deep, umami-rich ferments—like novel misos, shōyus and garums—made with all sorts of novel substrates, including many upcycled by-products like spent coffee grounds, brewer’s spent grain and pumpkin skin. As delicious and diverse as these ferments are, they represent only one part of our prospective toolbox. The categorisation framework points to other avenues, and could be used to structure and design future R&D projects. Engrafting target species, developing community chimeras and generating novel phenotypes could all offer exciting additional opportunities for novel fermentation beyond switching substrates.

Another tool outlined in the paper that could provide clues to direct innovation involves the mapping of what the authors call ‘fermentation space’—the possibility space for fermentation processes and products—according to similarities and differences among known microbial communities and substrates. This view offers both a partial record of what exists and also a prompt for what might be developed. By examining its gaps, we can begin to ask not only how different ferments have come to be and why they cluster, but also what kinds have yet to emerge. One such gap (‘Gap 1’ in Figure 3) exists in the space between classic fermented meat and legume products. Exploring this gap could be a useful starting point for developing further ways to umamify plant foods, and more generally to unlock new flavour, texture, and other functional combinations.

Figure 3: A simplified map of fermentation space, adapted from Figure 5 from Arrigan et al. 2024, that maps fermented foods based on microbial and substrate data. The focus is on the broad categories (meat, plant, and dairy) and the idea of two major “gaps” in fermentation space. Our rendering is not intended to be precise or scientifically valid, but rather an accessible way to show that certain areas of fermentation remain relatively unexplored.

v. Further challenges

Food cultures are dynamic and continually evolving. So the very concept of ‘novel fermentations’ might invite scrutiny. When does something stop being 'traditional' and become 'novel'—and who gets to decide? After all, many so-called traditional fermentations, like miso, have rich and varied histories that only exist as accumulations of past innovations. While miso is often thought of as a staunchly traditional Japanese ferment made from soybeans and kōji, its roots can be traced back to ancient China, and it has long been more varied than just combinations of these two components, morphing over the centuries as different ingredients, processes and cultural practices were incorporated. Novel misos made from ingredients like spent coffee grounds or brewer’s spent grain may best be thought of, therefore, less as an abrupt schism from tradition and more another iteration in a long continuum of biocultural experimentation.

This is where the value of this framework lies. Far from gatekeeping what is novel or not (a not particularly interesting question), it offers a structured way to understand fermentation as an ecological and evolutionary process, shaped by and shaping food culture. In doing so, it complements a dynamic view of food culture by providing a vocabulary for thinking about how that evolution might continue—and in which directions—in the future.

With this focus on dynamism and creativity comes responsibility—for example for safety. Novel fermentations involving unfamiliar combinations of microbes and substrates raise important safety considerations. New or evolved microbes may possess pathways that produce unknown or potentially harmful compounds. The same holds true for known microbes grown in new environments. Unexpected interactions between co-cultured species and novel ingredients can also lead to adaptive changes, enabling microbes to bypass established safeguards and produce undesirable metabolites. These risks highlight the need for more research into metabolite profiling, and the development of tools to predict and evaluate the safety of emergent fermentations. This is not only crucial for protecting public health, but also for ensuring that innovation proceeds responsibly.

Responsibility is also about larger ethical, political, and cultural questions. Even if culture is continually evolving, the ethical question of ownership remains. If today’s practitioners are merely continuing a long lineage of human and non-human tinkering—borrowing techniques and ingredients cultivated over generations—who, if anyone, owns novel fermentations? And who should benefit when these innovations are commercialised? These questions echo long-standing debates around and in biotechnology, including those surrounding the patenting of life and the biopiracy of biological resources. In the realm of novel fermentations, such concerns are just as salient. Who owns A. oryzae or the right to innovate on miso-making? Is it the traditional producers in Japan? The Japanese state? Diaspora communities who are pushing the boundaries of fermentation? Passionate and respectful newcomers? Any or all of the above and/or others? And how should it be decided?

Along these lines, the authors wonder how we might imagine more participatory and reciprocal ways of offering something back to communities from which traditional fermentation techniques are borrowed that is ‘beyond due crediting, doing our homework, and basic respect and sensitivity’. Perhaps innovative models of reciprocity, like profit-sharing or fermentation sovereignty funds, could be established to benefit the food cultures from which traditional ferments derive, particularly when they are profited from by more powerful institutions. Such initiatives would not be without their own political challenges of course—who invented miso, for example, and who gets to decide?—but might at least advance these important conversations in constructive ways.

The paper's authors also reflect on what a more reciprocal, participatory, and respectful science of fermentation could look like. One such example we would like to highlight is SILA, a recently founded Bachelor's programme in biology aimed at Greenlandic students at Ilisimatusarfik (The University of Greenland), structured around Greenlandic nature, science and culture. At SILA, scientific education and research is conducted by, with and for Indigenous communities, including around their numerous traditional fermented foods. The SILA team is building a science where knowledge isn’t just extracted, but rather co-created with its traditional stewards.

SILA represents one model of how fermentation, traditional and novel, can become a site for relational, place-based science—anchored in culture, ethics, and ecology. A beautiful example from SILA researchers is their recent paper exploring how garum can be used to cultivate new flavours and microbial dietary diversity from traditional Inuit foods like ptarmigan intestine. Could novel fermentations elsewhere also be a site for reimagining how science can engage well with culture, not just borrowing from the past and other cultures and not giving anything back, but building new forms of solidarity in the present and for the future? What, for example, might a SILA for different cultures and bioregions look like? What other such models for science and research might be possible?

There is still much to explore in the world of novel fermentations. The framework presented here offers one way to help navigate it—not as a rigid classification system, but as a more structured way of thinking about the diversity and surprising powers of microbial life. By viewing fermentation through the lens of community assembly and rational design, we gain tools not only for creating new flavours, but also for engaging with the ethical, cultural, and safety dimensions of innovation. In doing so, the framework invites deeper reflection—most notably, on how we might cultivate more meaningful and reciprocal forms of connection, exchange, and collaboration with fermentation practitioners across disciplines, communities, and traditions.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Taylor and Eliot wrote the article, with contributions and editorial feedback from Josh. Caroline and Josh co-wrote the original paper this article is based upon led by Benjamin Wolfe and Dillon Arrigan (Tufts University), with Angela Oliverio (Syracuse University).

Taylor created the header image and Figure 2, and adapted Figures 1 and 3 from the original paper.

Endnotes

[1] Not all instances of upcycling rely on fermentation, but many do.

[2] The paper specifically focuses on the fermentation of food ingredients into whole foods and beverages, and does not include precision bioreactor fermentation or synthetic biology techniques.

[3] Matthew M. Cleere et al. (2024), ‘New colours for old in the blue-cheese fungus Penicillium roqueforti’, NPJ science of food.

[4] William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi (1983), ‘The Book of Miso’, Ballantine Books: New York, USA.